Is AI smarter than we are or stupider than we are? Yes

This isn’t an AI newsletter per se, in the sense that I don’t always write about it. However, I do write about it fairly often, mostly because I don’t think there’s anything else happening — apart from maybe crypto — that blends the surprising and the terrifying and the confusing and the potentially evil so perfectly as AI. That’s the Torment Nexus sweet spot! (You can find out why I called the newsletter that in this post, in case you don’t know the story already). Is the kind of artificial intelligence — or whatever you want to call it — that we see all around us now an incredible technological advancement? No doubt about it. Regardless of what you think of AI’s current abilities or potential, it’s still mind-boggling to think of how far we have come in the three years since ChatGPT and other tools first appeared on the scene. Are they intelligent in any real sense of that word? Sure. Are they conscious? Who knows. Is AI an unalloyed good? Of course not. Does it spell doom for mankind as we know it? Maybe, but probably not.

I’m not here to take sides in the “Is AI Good Or Evil” debate, to be honest. There are people much smarter than me who already have both sides of that covered, and most of them (although not all) have a deeper understanding of the technology and its limits than I do. In fact, one of the things I find so fascinating about AI right now is that there is so much disagreement even within the field itself, and even among those who helped create the technology we are currently using, like former University of Toronto professor and former Google AI staffer Geoffrey Hinton and Meta chief technologist Yann LeCun and McGill University lecturer Yoshua Bengio. Are we close to AGI? Geoff says yes, Yann says no (and prominent AI critic Gary Marcus says hell no). Does AI pose a mortal danger to humanity as we know it? Yoshua and Geoff both say yes, Yann says no. I’ve written about this before, and also about the question of AI and consciousness.

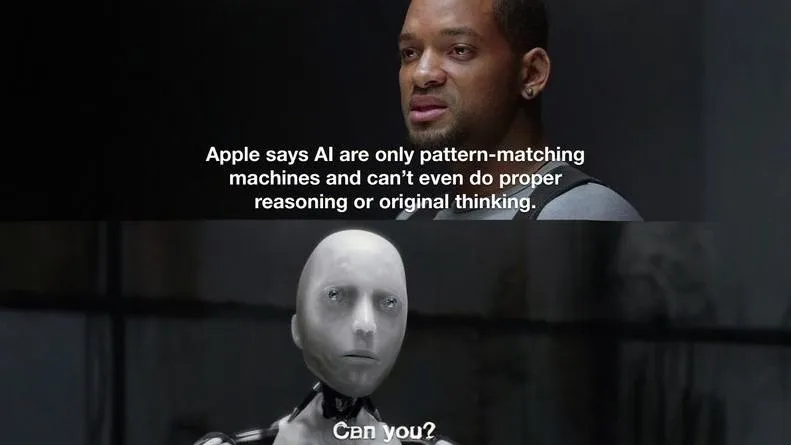

In the same vein, I was interested to see two recent studies of AI that seemed to point in completely opposite directions. In one, published by Apple’s Machine Learning Research project and titled The Illusion of Thinking, scientists raised some significant doubts about AI’s “intelligence,” pointing out that even the latest more sophisticated AI engines from companies like OpenAI and Anthropic and DeepSeek couldn’t solve — or took much longer than they should have to solve — a puzzle that an eight-year-old could probably figure out without too much trouble (a block and peg puzzle known as the Tower of Hanoi). They seemed to have a tough time with some other simple puzzles as well, including the “river crossing” puzzle, in which the test subject has to get three conflicting objects (fox, chicken, and bag of grain) from one bank to another even though they can only take two at a time. In fact, the AI engines had difficulty even after the researchers gave them clues that pointed towards the solution! Here’s a summary of the paper:

Through extensive experimentation across diverse puzzles, we show that frontier LRMs face a complete accuracy collapse beyond certain complexities. Moreover, they exhibit a counter-intuitive scaling limit: their reasoning effort increases with problem complexity up to a point, then declines. We found that LRMs have limitations in exact computation: they fail to use explicit algorithms and reason inconsistently. We also investigate the reasoning traces, studying the patterns of explored solutions and analyzing the models’ computational behavior, shedding light on their strengths, limitations, and ultimately raising crucial questions about their true reasoning capabilities.

Note: In case you are a first-time reader, or you forgot that you signed up for this newsletter, this is The Torment Nexus. You can find out more about me and this newsletter in this post. This newsletter survives solely on your contributions, so please sign up for a paying subscription or visit my Patreon, which you can find here. I also publish a daily email newsletter of odd or interesting links called When The Going Gets Weird, which is here.

AI: Bag of rocks or mathematical genius?

I’ve lost count of the number of references to this study that used it as conclusive evidence that AI is as stupid as a bag of rocks, and that the whole field is a fraud being perpetrated by oligarchs to enslave humanity, etc. etc. In a piece published in The Guardian, aforementioned AI critic Marcus — who has been raising doubts about AI since 1998 — wrote that the tech world was “reeling from a paper that shows the powers of a new generation of AI have been wildly oversold…. all but eviscerating the popular notion that large language models (LLMs, and their newest variant, LRMs, large reasoning models) are able to reason reliably.” What this means for society, Marcus concludes, is that “we can never fully trust generative AI” because its outputs are just too hit-or-miss (I couldn’t help noticing that he says we can never trust it period, not that we can’t trust it right now). Large-language models, he adds, will continue to have their uses, such as helping programmers write code, or helping people think through a problem, but “anybody who thinks LLMs are a direct route to the sort of AGI that could fundamentally transform society for the good is kidding themselves.”

So that was one of the recent studies that caught my eye. The second was a report from what Scientific American described as a “secret meeting of thirty of the world’s most renowned mathematicians,” which occurred in Berkeley, California last month. Their purpose: to throw some of the world’s hardest math problems at OpenAI’s latest “reasoning” AI engine in an attempt to stump it. Here’s how Scientific American described it:

On a weekend in mid-May, a clandestine mathematical conclave convened. Thirty of the world’s most renowned mathematicians traveled to Berkeley, Calif., with some coming from as far away as the U.K. The group’s members faced off in a showdown with a “reasoning” chatbot that was tasked with solving problems they had devised to test its mathematical mettle. After throwing professor-level questions at the bot for two days, the researchers were stunned to discover it was capable of answering some of the world’s hardest solvable problems. “I have colleagues who literally said these models are approaching mathematical genius,” says Ken Ono, a mathematician at the University of Virginia and a leader and judge at the meeting.

The magazine goes on to describe how Epoch AI, a non-profit that does AI benchmarking, was asked last year by OpenAI to come up with 300 math questions whose solutions had not yet been published anywhere that an LLM could be expected to have indexed them, as part of a project that Epoch called Frontier Math. As Scientific American notes, many AI engines can answer math questions, even difficult ones, but the questions that Epoch came up with were deliberately designed to be dissimilar to other questions that AI engines might have been trained on — as a way of testing their ability to reason. When asked to solve the 300 new questions, even the most successful of the LLMs tested were able to solve less than 2 percent of them, which most observers concluded was evidence that they lacked an ability to generalize — in other words, to reason. But the results from the mathematician’s conclave were very different.

Epoch AI started working on the highest level of math problems, ones that might even stump practicing academics, on the understanding that any mathematician who came up with a problem that the o4-mini couldn’t solve would get a $7,500 reward. As Scientific American describes it, the decision to have an in-person meeting was designed to speed things up, and also to make it easier for the human mathematicians to confer on which problems they should give the AI. The 30 attendees were split into groups of six, and for two days they competed to devise problems that they could solve but would trip up the AI reasoning bot. Those who participated had to sign a nondisclosure agreement requiring them to communicate solely via the messaging app Signal, since conventional email might be captured by the AI and used for training purposes.

Impressive or alarming, or both?

One of the mathematicians who participated in the Epoch test described what happened next, when he gave o4-mini a difficult problem:

“I came up with a problem which experts in my field would recognize as an open question in number theory—a good Ph.D.-level problem,” he says. He asked o4-mini to solve the question. Over the next 10 minutes, Ono watched in stunned silence as the bot unfurled a solution in real time. The bot spent the first two minutes finding and mastering the related literature in the field. Then it wrote on the screen that it wanted to try solving a simpler “toy” version of the question first in order to learn. A few minutes later, it wrote that it was finally prepared to solve the more difficult problem. Five minutes after that, o4-mini presented a correct solution. “And at the end, it says, ‘No citation necessary because the mystery number was computed by me!’” Ono jumped onto Signal and alerted the rest of the participants. “I was not prepared to be contending with an LLM like this,” he says, “I’ve never seen that kind of reasoning before in models. That’s what a scientist does. That’s frightening.”

The group eventually came up with 10 questions that o4-mini couldn’t answer, but all of the researchers said they were surprised — and maybe even disturbed — by how AI had progressed in solving such problems in just a year. A mathematician at the London Institute for Mathematical Sciences and an early pioneer of using AI in math told Scientific American that the questions it solved were equivalent to “what a very, very good graduate student would be doing — in fact, more.” And the AI was much faster than a grad student, since it took only a few minutes to do what might have taken a human expert weeks or months. “I’ve been telling my colleagues that it’s a grave mistake to say that generalized artificial intelligence will never come, [that] it’s just a computer,” Ono said. “I don’t want to add to the hysteria, but in some ways these large language models are already outperforming most of our best graduate students in the world.”

So which is it: Are advanced AI engines so stupid that they can’t solve a child’s puzzle, or are they mathematical geniuses doing PhD-level computation in minutes? The answer is both. How is that possible? One possibility is that math is a discipline that — much like programming — follows certain immutable rules, and once you know the rules then problems boil down to simple (or not so simple) computation, which AI engines have bucket loads of. Moving wooden blocks around from peg to peg, however, or thinking through how to use a boat to move conflicting objects across a river, requires an understanding of physical movement and how objects interact with the world. This is something that even sophisticated AI engines have trouble with — at least so far — and this becomes abundantly obvious when you watch an AI-generated video that is supposed to represent a gymnast or a ballet dancer. And that’s why Apple’s AI research lab chose to use puzzles instead of mathematical problems.

Both of these things arguably constitute reasoning on some level, but they are different kinds of reasoning — they require different skills. Does that mean that AI engines will only ever be good at math, and will never understand the physical world, or how human beings move through it and interact with it? I think that kind of conclusion requires a big leap that I, for one, am not willing to take. Just look at how the earliest AI video of Will Smith eating spaghetti compares to some of the latest AI videos, which I would argue are indistinguishable from reality (unless written or printed text appears in the video, which is another stumbling block for current AI engines). If that is how much AI has changed — or learned, if you will — in just that amount of time, what are things going to look like two years or five years or ten years from now? That is frightening on one level, but also fascinating on another. Welcome to the Torment Nexus!

Got any thoughts or comments? Feel free to either leave them here, or post them on Substack or on my website, or you can also reach me on Twitter, Threads, BlueSky or Mastodon. And thanks for being a reader.