Netscape's birth and some thoughts about the web

Note: In case you are a first-time reader, or you forgot that you signed up for this newsletter, this is The Torment Nexus. You can find out more about me and this newsletter in this post. This newsletter survives solely on your contributions, so please sign up for a paying subscription or visit my Patreon, which you can find here. I also publish a daily email newsletter of odd or interesting links called When The Going Gets Weird, which is here.

Before I begin, I would just like to apologize in advance to anyone who is reading this and is in their 20s or 30s (or possibly 40s) and doesn’t remember the launch of the first Netscape web browser in 1994. I realize that for some of you, writing about this and my personal experience of it is probably a little like how I felt when my grandfather mused about life during “The Great War” (it didn’t get called World War I until after World War II, obviously, because no one knew there would be a second one). So if you have as much interest in the early days of the world wide web as you do in the Great Pyramid of Egypt then please move on to TikTok or whatever and I will see you later.

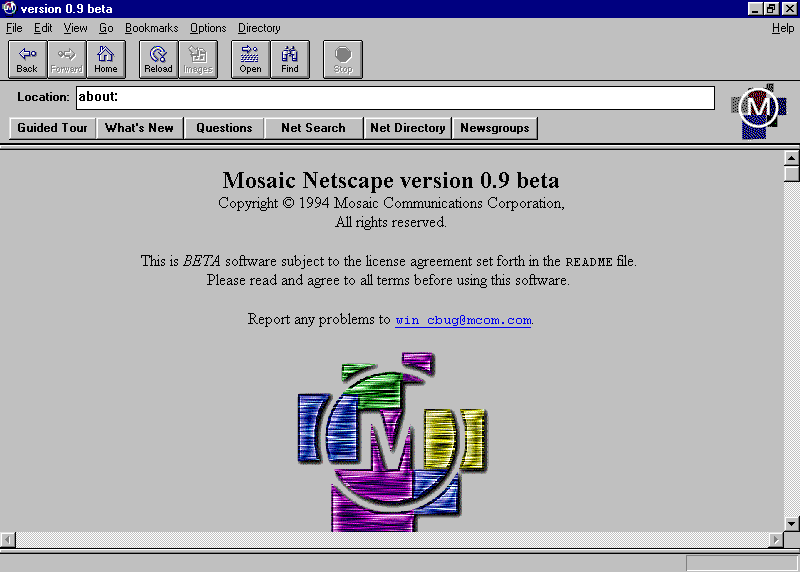

I was all set to write about something else this week for The Torment Nexus — which I will keep to myself, since I may write about it at a later date — and then I saw a link to a blog post from Jamie Zawinski, a programmer who was working at Netscape at the time (he is now the the proprietor of the DNA Lounge, a San Francisco nightclub). Zawinski writes about launching Mosaic Netscape 0.9 on October 13, 1994 (okay, I am a little late for the actual anniversary but it is what it is) and describes it in this way:

“We sat in the conference room in the dark and listened to different sound effects fired for each different platform that was downloaded. At some point late that night I wandered off and wrote the first version of the page that loaded when you pressed the “What’s Cool” button in the toolbar. (A couple days later, Jim Clark would go ballistic in a company-wide email because I had included a link to Bianca’s Smut Shack.)”

As Zawinski explains, Mosaic 0.9 was the first release of the Netscape browser that was available to the general public — an updated version of the Mosaic browser that Marc Andreessen created when he was still a student at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (of course, Illinois is a real technological superpower, as I'm sure most of you know.) Marc got hired by Jim Clark to create Netscape, which in turn spawned Firefox — which came from Mozilla, a nonprofit that Jamie Zawinski also helped launch after leaving Netscape — as well as Microsoft’s Internet Exploder (sorry, I mean Explorer) and Google Chrome and many others.

A light in a darkened room

I should note here that, because I am an ancient shell of a human being with dust in my veins, I honestly can’t remember whether my first experience of the graphical web came via Andreessen’s Mosaic or the Netscape 0.9 release (Trivia: Mosaic wasn't the first graphical web browser – it was preceded by one Tim Berners-Lee designed, as well as one called Erwise and one called ViolaWWW). In a way, it doesn’t really matter which one I used — the point is that it was like a light suddenly coming on in a darkened room. As some of you will remember, the internet until then was green text on a black screen, typing in commands in order to connect to a distant Gopher or Archie or FTP server.

Just to provide even more context that many of you probably don’t care about, I was interested in the internet in the early 1990s for three reasons: 1) There were supposed to be photos of Baywatch star (and Canadian icon) Pamela Anderson on there; 2) I had read that NASA was required by law to put all of its space photos on the internet, and 3) An infamous multiple-murder case was underway in Canada — one of the few husband-and-wife teams in history, as it turned out — but there was a publication ban, and I had heard that some US publications were posting information about it that was unavailable to me in Toronto (all honourable reasons for getting online, I’m sure you will agree).

In any case, I don’t think an ancient serf seeing an illustrated manuscript for the first time in the 11th century would have been any more gobsmacked than I was at Netscape. Yes, there were things like America Online and Compuserve before that, and I had tried most of them. But I felt that they were like a children’s playground with 10-foot-high walls — you couldn’t even see the real internet from there, let alone actually interact with it. Not long after Netscape launched, the pieces of paper (yes, paper) that I kept with Gopher and FTP addresses listed on it was replaced by lists that started with http://.

A way to reach outwards

I wound up creating my own website, which I eventually called A Complete Waste of Time (you can see a recreated version of it here, and most of the links still work). Since I was at the time a stock-market reporter, I set up a separate page where people could find stock-quote services (Worth magazine’s Site of the Day in 1995, thank you very much). A friend and I even tried to get the newspaper we worked at then to launch a public-facing news site on the web, but there was no interest in doing so until much later — the year 2000, to be precise, when I joined the live news team as the online business columnist.

For me, having a website of my own and a blog (which I started in 2005 or so) felt like the world had opened up. I could reach out to others with similar interests directly and they could reach back. I could have online debates and link to people like Dave Winer and Dan Gillmor and Mike Masnick, and keep track of my favourite sites using Del.icio.us and find new ones with tools like Stumbleupon (Brief aside: Cofounded by Garrett Camp, a Calgarian who later cofounded Uber). After running social media for the Globe for a couple of years, I joined my friend Om Malik’s blog network, Gigaom (RIP).

Here’s the existential part (in case you thought I was never going to get there): not long after I joined Gigaom, Wired magazine published a cover story called The Web Is Dead, in which editor-in-chief Chris Anderson and Michael Wolff (yes, that Michael Wolff) argued that the web was the past, and the future was mobile apps like Facebook and Twitter and Pandora (RIP). "As much as we love the open, unfettered Web, we’re abandoning it for simpler, sleeker services that just work," the article stated. "Today the Internet hosts countless closed gardens; in a sense, the Web is an exception, not the rule."

This triggered an avalanche of skepticism, including some from us at Gigaom (and some from the web's creator). How could the web be dead? An overreaction at best, and a deliberate distortion at worst, we thought. After all, people were still using browsers, right? Websites still existed, right? Weren't most apps just fancy re-skinned websites?

I think there was a lot more truth to that story than I admitted at the time. Yes, there are still websites — which in many cases only exist to convince you to download the site’s smartphone app, whether it’s Twitter or Substack or TikTok or the app for Dunkin Donuts or your bank or some airline, and more recently for your dishwasher and stove. Those apps not only come from closed app stores (although the EU is trying to change that) but they all have built-in “features” that track you and your behavior, and force you into certain predetermined paths that lead to increased monetization. It’s true that under the hood, many of these apps are just tarted-up HTML (in other words, websites) but they are open in the same way that a cemetery or an ant trap is open.

A web of silos

From an open expanse seemingly without end, there are now just massive silos with various names: Facebook makes it difficult to crosspost from other services or apps and has tried hard to get people to stop linking out at all (and won't let you post news stories if you are in Canada for reasons I don't have time to go into). Instagram won't even let you put an HTML link in your post, which seems too absurd to be true in the year of our lord two thousand and twenty-four — you have to use a third-party app to add links that people can get to, but only if they click on a link in your bio. Even Google, which used to be the standard bearer for the open web, has become very silo-ish with links generated by its own services, which it promotes in a carousel at the top of its results.

Yes, there are still open sites and services like Reddit (although it has cracked down on its volunteer moderators to make it easier to monetize the content its users post), and some sites like Techdirt and Kottke.org — and of course Dave Winer's Scripting.com — still exist. But it is a small crowd. It's like a small desk of indie filmmakers at the back of a cavernous convention centre filled with booths for Paramount and 20th Century Fox. If there is a ray of hope or silver lining at all, for me at least, it is the "fediverse" of apps like Mastodon and Lemmy and Peertube (alternatives to Reddit and YouTube respectively). Links to my social accounts on Mastodon and BlueSky are below.

Perhaps the most surprising ray of hope in all of this is that Threads has embraced federation, and Mark Zuckerberg and Adam Mosseri have said all kinds of good things about the need for openness. Do they believe them, or is this all just marketing? Stay tuned. Thanks for coming to my Ted Talk. And if you know of any open web services or things I should know about, please share them with me! Ways to get in touch with me are at the end of this post.

Got any thoughts or comments? Feel free to either leave them here, or post them on Substack or on my website, or you can also reach me on Twitter, Threads, BlueSky or Mastodon. And thanks for being a reader.