On Nepal's Discord election and social-media driven uprisings

If you've been following the online discourse at all (and I would encourage you not to do too much of that, especially now) you may have seen a number of journalists and other commentators arguing that the blame for a big part of the unrest that we are seeing in the United States should be laid at the feet of social media (if social media had feet). Tools like X and Instagram and TikTok and Bluesky, or so the theory goes, serve only to inflame political divisions and empower the loudest and stupidest opinions out there. When combined with the bots — some of which appear to be driven by foreign agents who want to sow discord wherever possible — and the algorithms that seek engagement above all else, the whole system becomes a chaos engine, critics say. As some loyal readers of The Torment Nexus may know, I don't really buy this argument, at least not entirely, and I went into some of the reasons why in a recent piece.

Given all of this debate, I was fascinated to watch what happened recently in Nepal. You can read a lot more about the background to the events there at the usual news sites, including the New York Times and CNN, but the short version is that a popular uprising appears to have been ignited in part by the government's decision in early September to ban more than 25 social-media platforms, including Facebook and YouTube, both of which are very popular with Nepalese citizens, especially younger people. The nominal reason for the ban was that the social platforms had failed to meet a requirement to register with the government — something that a number of other countries including Turkey and Brazil have also implemented in the past. Nepal's government justified the rule and the subsequent ban in the same way that these other countries did: by arguing that the social-media platforms are filled with fake news and hate speech.

Instead of taking this ban quietly, many Nepalese citizens — including what appear to have been a large number of young people — chose to riot. According to a number of reports, thousands of ordinary citizens stormed the country's parliament in the capital city of Kathmandu and lit a number of buildings on fire, including the parliament building and the Supreme Court, threw rocks at police, and generally caused havoc. Some protesters hurled stones at Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli's house in his hometown of Damak and later burned it. As many as 70 people are reported to have died in the riots, and several areas of Kathmandu were placed under a curfew. After an emergency meeting by the government's senior ministers in the first week of September, the social-media ban was lifted, but that didn't seem to be enough for the protesters. Many of those interviewed said that the real problem was not the ban but corruption.

Protesters rioting is not anything new, either in Nepal or anywhere else. Nor is it uncommon for these protests to be about a number of different complaints, rather than being triggered by a single event. But what happened next is unusual: not only did the prime minister step down as a result of the ban and the aftermath, but out of the chaos emerged a social project unlike anything we have seen in modern times. Organizers involved in the protests joined with existing advocacy groups, and they started coordinating their proposals for the future of Nepal using Discord, a social platform that first became popular with gamers (some protesters also reportedly used BitChat, a service started by former Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey, which uses Bluetooth rather than cellular signals and is therefore theoretically less traceable). And the military in Nepal — which took control of the country following the prime minister's resignation — actually reached out to the protesters and asked them for their help. From the Times:

With the country in political limbo and no obvious next leader in place, Nepalis have taken to Discord, a platform popularized by video gamers, to enact the digital version of a national convention. “The Parliament of Nepal right now is Discord,” said Sid Ghimire, 23, a content creator from Kathmandu, describing how the site has become the center of the nation’s political decision making. The conversation inside the Discord channel, taking place in a combination of voice, video, and text chats, is so consequential that it is being discussed on national television and live streamed on news sites. The channel’s organizers are members of Hami Nepal, a civic organization, and many of those participating in the chat are the so-called Gen-Z activists who led this week’s protests.

Note: In case you are a first-time reader, or you forgot that you signed up for this newsletter, this is The Torment Nexus. You can find out more about me and this newsletter in this post. This newsletter survives solely on your contributions, so please sign up for a paying subscription or visit my Patreon, which you can find here. I also publish a daily email newsletter of odd or interesting links called When The Going Gets Weird, which is here.

Ghosts of the Arab Spring

In effect, it appears that instead of just seizing power themselves, senior officials in the Nepalese military allowed the members of the Discord channel to suggest the names of some potential nominees for interim leader of the government (this is a critical point, and one I will come back to). Those names included some former political candidates, as well as the former director of Nepal's national power company. Many of those who were suggested as potential interim leaders took part in meetings with dissidents in the Discord chat room that lasted for hours, according to the Times. In the end, the group on the server — which numbered as many as 140,000 at one point — came together to nominate Sushila Karki, the former chief justice of Nepal's Supreme Court, who agreed (reluctantly) to meet with the chiefs of the military to find a way forward. She has said she will be only an interim leader, and elections will be held in March.

Not surprisingly, Nepal's major political parties have complained that the Discord-led process by which Karki became prime minister is unconstitutional and should not stand. But given the riots and loss of life involved, no one seems to want to push things too aggressively. It is definitely unprecedented — not just in Nepal, but anywhere else — for a small group of protesters to run what amounts to an election for an interim leader to head a country of 30 million people on a Discord server with about 150,000 people on it, just a matter of days after setting fire to Nepal's parliament buildings. As the Times describes it, the process was not just unusual or unconstitutional, but also highly chaotic:

“The point was to simulate a kind of mini-election,” said Shaswot Lamichhane, a channel moderator who helped establish the server and has represented the group in meetings with the military. Mr. Lamichhane graduated from high school a few months ago. “It happened so quickly,” said Samip Lamsal, 22, a recent college graduate in Kathmandu, who joined parts of Wednesday’s forum, calling the channel’s discussions “very disorganized,” and like a “random social media call.” Anyone could join the channel, making it easily infiltrated by trolls or people from outside Nepal. Moderators had to tamp down calls for violence. And because anyone could speak up, conversation were often a garbled mess. “Please decide on a representative right now — WE DO NOT HAVE TIME,” the moderators told the channel on Wednesday before settling on Ms. Karki.

Will any of this — either Karki's status as interim leader, or the apparent power that some of the Gen Z protesters who started the Discord server hold — be in place a month from now? Six months from now? I have no idea. As Steven Feldstein from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace said to the Times, the use of a platform like Discord at such a scale is fairly unprecedented, but in other similar cases where social platforms played a role in a popular protest, they have proven to be much more effective at channeling unrest than in planning for the aftermath of a government's overthrow. Or as Feldstein put it, social media may be highly effective at "phase one" of social and political movements — that is, turning people out to protests — but it has been less successful in creating "a stable political structure in the long term."

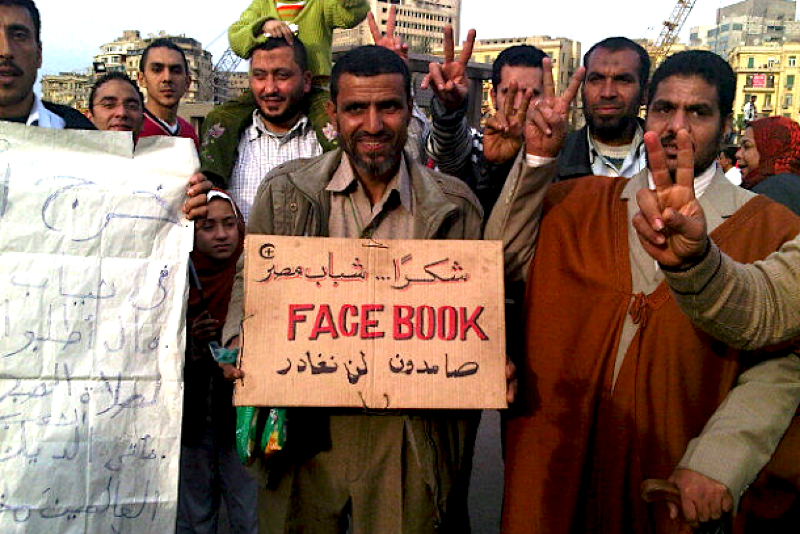

I'm probably not the only one who watched the escalating Nepalese situation and thought of a much earlier social-media powered uprising: namely, the political revolution in Egypt in 2011, part of the so-called Arab Spring, when riots — fueled in part by Facebook and Twitter (as it was then) — escalated and led to the fall of the government of president Hosni Mubarak. In the early days of this revolution, it seemed as though social media had achieved an unprecedented victory; protesters thanked both Facebook and Twitter for the role they played, and many observers (including me) argued that this showed the power of social media, the way it democratized access to information, and allowed people from across the country — and around the world — to unite in a common cause.

The Arab Winter

Unfortunately for the Egyptians who came together using Facebook and Twitter — and for those who cheered them on via Twitter — this social-media-powered victory was short-lived. After Mubarak resigned, the military took control of the country and there was an election in 2012, in which Mohamed Morsi, the former leader of the group Muslim Brotherhood, was elected. In 2013, the military deposed Morsi and cracked down, killing thousands. The next year, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, a former field marshal in the army, won an election in a landslide — a landslide that was widely viewed as rigged. The constitution was amended to entrench the military as the real governing body of the country, and there were widespread restrictions on dissent of any kind, including a ban on gatherings of more than 10 people. Similar acts of repression — and worse — occurred in some or all of the other countries that were part of the "Arab Spring," including Syria, Libya, Tunisia and Yemen. Per Wikipedia:

The wave of initial revolutions and protests faded by mid to late 2012, as many Arab Spring demonstrations were met with violent responses from authorities, pro-government militias, counterdemonstrators, and militaries. These attacks were answered with violence from protesters in some cases. Multiple large-scale conflicts followed: the Syrian civil war; the rise of ISIS, insurgency in Iraq and the following civil war; the Libyan Crisis; and the Yemeni crisis and subsequent civil war. While leadership changed and regimes were held accountable, power vacuums opened across the Arab world. Ultimately, it resulted in a contentious battle between a consolidation of power by religious elites and the growing support for democracy in many Muslim countries. Some referred to the succeeding and still ongoing conflicts as the Arab Winter.

Obviously, we all hope that this doesn't happen in Nepal. But it's worth remembering that the only reason the Discord protesters had any power or authority to nominate an interim leader is because the military gave it to them. And just because the nominee they chose — and the cabinet ministers who were also selected on Discord — have formed an interim government is no guarantee that future elections will produce the result Gen Z protesters are hoping for, or that the government that is eventually elected will do anything about the concerns that those protesters had with respect to systemic corruption etc. As my former CJR colleague Jon Allsop noted in his overview of the situation, "the narrative of this story might seem to trace an arc from techno-dystopia to techno-utopia. But the reality, as usual, is more complicated." There have even been reports that the former monarch whose family ruled Nepal before democracy arrived in 2008 might try to use this opportunity to get involved again.

In the aftermath of the failed Arab Spring movements across much of the Arab world, sociologist Zeynep Tufekci wrote about how social media can be a double-edged sword: it can help like-minded people find each other and build momentum for change, but at the same time, this same ease of organizing can make it more difficult for protest groups to become as strong and cohesive as they need to be in order to survive over long periods of time. Old-fashioned political movements took years — or even decades — to develop and build an organization, and that helped them create the infrastructure that allowed them to survive. To put it somewhat differently, social media tools like Twitter and Discord and even Facebook can be great at making it easy for large groups of like-minded people to come together quickly and share their thoughts (including, of course, people with bad intentions as well as good ones). But it can't overthrow an army.

Got any thoughts or comments? Feel free to either leave them here, or post them on Substack or on my website, or you can also reach me on Twitter, Threads, BlueSky or Mastodon. And thanks for being a reader.