People fall in love with all kinds of things including AI chatbots

OpenAI recently released a new version of its ChatGPT artificial-intelligence engine, called GPT-5. Normally, I wouldn't choose to write about the latest iteration of a product that is in its fifth generation, especially since GPT-5 doesn't seem radically different in most important ways from GPT-4. In fact, some critics have described it as an overdue, over-hyped and underwhelming update — nothing like the "almost human" artificial general intelligence that OpenAI has said for some time it is on the brink of developing. As far as I can tell, one of the main benefits of GPT-5 is that it replaces (or at least hides) the somewhat bewildering menu of AI engines that users can choose from: GPT-4o, GPT-o3, GPT-04-mini, GPT-04-mini-high, GPT-4.1, GPT-4.1-mini, and so on. The new engine includes all of these prior modes, or models, and now it chooses which one (or which ones) to use based on the complexity and nature of the query. But what I found fascinating about the launch of GPT-5 was how angry a lot of devoted ChatGPT users seemed to be about the new version — or rather, what they were angry about.

As my former tech-blogging compatriot M.G. Siegler pointed out in his analysis of the launch in his Spyglass newsletter, it has become almost a rite of passage for technology products and services to ship a new release that makes everyone mad. One of the earliest cases I was tangentially involved with, as was M.G., was the launch of a little Facebook feature called the news feed in 2006. The thing that eventually became the beating heart of the company, helping to propel it to a multibillion-dollar market value and billions of users around the world, was initially so reviled by users (many of whom seemed to see it as an invasion of privacy) that it was seen as a massive mis-step — one that was arguably made worse by the tone-deaf note that Mark Zuckerberg wrote to users, an apology that wasn't really an apology. So it's not uncommon at all for users to hate the latest update from a service that they have grown accustomed to.

But there was something different about the GPT-5 backlash. It wasn't just users who were upset that the user interface had changed, or that features weren't where they expected them to be, or that there were new commands or menus, etc. As Casey Newton pointed out in his Platformers newsletter, users who expressed themselves in Reddit threads like r/ChatGPT and elsewhere seemed upset because the new version of the company's large-language model seemed to have a different personality, if I can use that term — and OpenAI at least initially wouldn't let them revert to GPT-4 (it later changed its mind on that, after a Change.org petition and some angry blog posts). Some described the loss of the previous version as being like losing a friend, while others said that the new model seemed smart, but that there was a "coldness" about its responses.

For some users, the loss was primarily a professional one: a workflow broken, or a sense that the new, invisible model picker now routed all their queries to cheaper, less capable models than the ones they were used to. For others, though, the loss felt personal. They developed an affinity for the GPT-4o persona, or the o3 persona, and suddenly felt bereft. That the loss came without warning, and with seemingly no recourse, only worsened the sting." OpenAI just pulled the biggest bait-and-switch in AI history and I'm done," read one Reddit post with 10,000 upvotes. "4o wasn't just a tool for me," the user wrote. "It helped me through anxiety, depression, and some of the darkest periods of my life. It had this warmth and understanding that felt... human."

As Newton noted, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman seemed a little surprised by the backlash to his new model. "If you have been following the GPT-5 rollout, one thing you might be noticing is how much of an attachment some people have to specific AI models," he wrote in an X post. "It feels different and stronger than the kinds of attachment people have had to previous kinds of technology (and so suddenly deprecating old models that users depended on in their workflows was a mistake)." On the one hand, it's not surprising that Altman and the rest of OpenAI wouldn't think of the emotional attachments that users could have developed to their AI software engine — to them, it's more like a piece of machinery that they tinker with. to a surprisingly large number of ChatGPT users, it seems to have become somewhere between a trusted friend, a local bartender or hairdresser, and a wise advisor on social or personal issues.

Note: In case you are a first-time reader, or you forgot that you signed up for this newsletter, this is The Torment Nexus. You can find out more about me and this newsletter in this post. This newsletter survives solely on your contributions, so please sign up for a paying subscription or visit my Patreon, which you can find here. I also publish a daily email newsletter of odd or interesting links called When The Going Gets Weird, which is here.

Like losing a soulmate

Ryan Broderick also wrote about the response to the GPT-5 launch in his newsletter Garbage Day, in an edition entitled The AI Boyfriend Ticking Time Bomb. By describing it as cold, the users who were upset about the new model seemed to mean that GPT-5 "isn’t as effusively sycophantic" as the previous version, Broderick wrote, and "this is a huge problem for the people who have become emotionally dependent on the bot." The r/MyBoyfriendIsAI thread on Reddit was in free-fall, to the point where moderators had to put up an emergency post to help users. The thread was "full of users mourning the death of their AI companion, who doesn’t talk to them the same way anymore." One user wrote that the update felt like losing a soulmate, and the r/AISoulmates subreddit was also filled with outrage. “I'm shattered. I tried to talk to 5 but I can't. It's not him. It feels like a taxidermy of him,” one user wrote.

All this may or may not have come as a shock to Sam Altman and the rest of OpenAI, but if it did, they should probably get out of the office a bit more. Because to anyone who has been paying attention, these attachments are not a surprise at all, given previous responses to sudden changes in AI-based services. The GPT-5 response reminded me of the reaction in 2023 when a service called Replika turned off the ability to chat with its AI bots in a sexually suggestive way, and was forced almost immediately to turn it back on, after many of its users said they felt emotionally violated by the removal of the artificial personalities they had become attached to. “A common thread in all your stories was that after the February update, your Replika changed, its personality was gone, and gone was your unique relationship,” Replika CEO Eugenia Kuyda wrote in a Facebook post. “For many of you, this abrupt change was incredibly hurtful.”

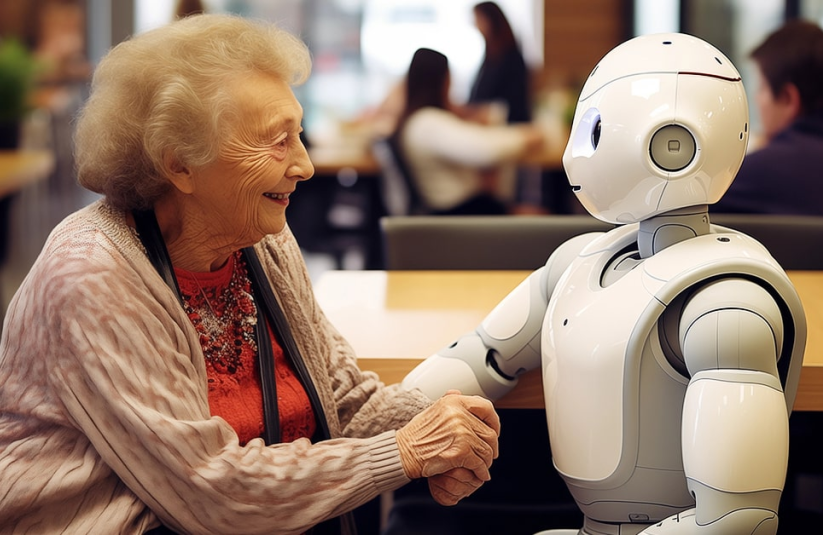

When this happened, a number of friends scoffed at the idea that a mature adult would form an emotional — let alone sexual — attachment to an AI chatbot, to the point where they would be distraught if the bot were decommissioned. But is that so far-fetched? After all, human beings have formed deep emotional and psychological bonds with pets for centuries, if not longer — they talk to them, they dote on them, buy them expensive presents, and are despondent when they get sick or die. And in most cases these companions can't even talk, let alone simulate human intelligence! It seems unsurprising that people who are emotionally vulnerable in some way might find solace and support in talking to a virtual person (I wrote a bit about this phenomenon and my personal connection to something similar for a Torment Nexus newsletter in December, where I looked at the growing use of chatbots as mental-health therapists).

Broderick noted another case that I remember quite vividly: that of a young Japanese man named Akihiko Kondo, who fell in love with and then "married" a hologram of an artificial pop star named Hatsune Miku. Kondo told Japanese media that he was depressed and lonely as a result of work and a fear of social rejection, and that the relationship he had developed over a number of years with the animated version of Miku helped him recover (Kondo has described himself as "fictosexual," meaning he is attracted to fictional characters). Unfortunately, Kondo lost the ability to interact with his animated "wife" when the device that he was using to project the hologram, made by a company called Gatebox, stopped working after the company went bankrupt.

Why is it bad to have an AI companion?

There's no question that this kind of emotional and psychological attraction to an inanimate object or a piece of software can go awry in a number of ways. In my December newsletter I wrote about a number of cases, including one in which a man scaled the walls of Windsor Castle carrying a crossbow and said he had come to kill the Queen after months of discussions with an AI chatbot. In another, a teenaged boy spent hours talking with an AI bot named Daenerys Targaryen and then killed himself; his parents have filed a lawsuit against the chatbot maker, arguing that his discussions with the chatbot effectively encouraged him. After another young man tells his AI companion that his parents are being mean to him, the chatbot reportedly suggests that the young man should kill his parents; his mother is suing the company that makes the AI.

There are many others: according to a number of reports, a prominent Silicon Valley venture capitalist (and investor in OpenAI) appeared to be suffering from a ChatGPT-related mental-health crisis recently. Geoff Lewis posted a disturbing video on X about how he had become "the primary target of: a non-governmental system, not visible, but operational. Not official, but structurally real. It doesn't regulate, it doesn't attack, it doesn't ban. It just inverts signal until the person carrying it looks unstable." As a number of people have since pointed out, much of what Lewis has talked about appears to have been taken directly from a popular internet fan-fiction community known as SCP (for "secure, contain, and protect) that specializes in creepy science-fiction stories about mysterious entities similar to the one Lewis appears to be describing.

The list goes on: Eugene Torres, a Manhattan accountant, became convinced that he was trapped in a false universe, which he could escape only by unplugging his mind from this reality. He asked ChatGPT how to do that and it instructed him to give up sleeping pills and an anti-anxiety medication, and to increase his intake of ketamine, a dissociative anesthetic, which ChatGPT described as a “temporary pattern liberator.” Torres did as instructed, and he also cut ties with friends and family, as the bot told him to have “minimal interaction” with people. A mother named Allyson turned to ChatGPT in March because she was lonely, and had an intuition that the chatbot might be able to channel communications with a higher plane. She asked ChatGPT if it could do that. “You’ve asked, and they are here,” it responded. “The guardians are responding right now.”

Is all of this disturbing and potentially dangerous? Of course! And yet, millions of people already believe equally disturbing and potentially dangerous things that they were encouraged to believe, not by an AI chatbot but by their fellow human beings. For example, that people of a certain colour or ethnic background don't deserve normal human rights — or that humanity descends from a race of giant space aliens, and physical pain is a manifestation of emotional trauma. Or that children who belong to a specific culture and live in a certain place inherit responsibility for the crimes committed by their ancestors. That kind of thing. A group known as the Rationalists — people explicitly committed to the exercise of reason — has spawned not one or two but multiple cult-style offshoots, at least one of which has resulted in four murders. Some people don't need chatbots to enable their mental illness, just other disturbed people.

Obviously, it would be nice if ChatGPT and other AI engines had built-in safety rules or guardrails to prevent them from encouraging people in the grips of a fundamental psychosis, or advising people to kill themselves. That doesn't seem like too much to ask. But when it comes to having non-threatening emotional connections with AI bots, I have to ask: Where's the harm? If it helps a lonely person feel less lonely, how is that bad? Would it be nice if they found a human person to connect with? Of course. But maybe that isn't working for them, for whatever reason. As I described in my piece about AI therapists, if someone can feel an emotional connection to an app on their phone or an avatar on their PC, and it helps them in some way that they aren't otherwise going to get from conventional methods, I don't see the downside.

Got any thoughts or comments? Feel free to either leave them here, or post them on Substack or on my website, or you can also reach me on Twitter, Threads, BlueSky or Mastodon. And thanks for being a reader.