Should we be afraid of AI? Maybe a little

Almost exactly a year ago, I wrote a piece for The Torment Nexus about the threat of AI, and more specifically what some call "artificial general intelligence" or AGI, which is a shorthand term for something that approaches human-like intelligence. As I tried to point out in that piece, even the recognized experts in AI — including the forefathers of modern artificial intelligence like Geoffrey Hinton, Yann LeCun (who now works at Meta), and Yoshua Bengio — can't seem to agree on whether AI actually poses an imminent danger to society or to mankind in general. Hinton, for example, who co-developed the technology behind neural networks, famously quit working on AI at Google because he said he wanted to be free to talk about his concerns around artificial general intelligence. He has said that he came to believe AI models such as ChatGPT were developing human-like intelligence faster than he expected. “It’s as if aliens have landed and people haven’t realized because they speak very good English,” he told MIT.

LeCun, however, told the Wall Street Journal that warnings about the technology’s potential for existential peril are "complete B.S." LeCun, who won the Turing Award — the top prize in computer science — in 2019, says he thinks that today’s AI models are barely even as smart as an animal, let alone a human being, and the risk that they will soon become all-powerful supercomputers is negligible at best. LeCun says that before we get too worried about the risks of superintelligence, "we need to have a hint of a design for a system smarter than a house cat,” as he put it. There are now large camps of "AI doomers" who believe that Hinton is right and that dangerous AGI is around the corner, and then there are those who believe we should press ahead anyway, and that supersmart AI will solve all of humanity's problems and usher us into a utopia, a group who are often called "effective accelerators," usually shortened to "e/acc."

In addition to OpenAI's ChatGPT and Google's Gemini, one of the leading AI engines is Claude, which comes from a company called Anthropic, whose co-founders are former OpenAI staffers, including CEO Dario Amodei. The company's head of policy, Jack Clark (formerly head of policy at OpenAI) recently published a post on Substack titled "Technological Optimism and Appropriate Fear," based on a speech he made at a recent conference about AI called The Curve. Although he didn't come to any firm conclusions about the imminent danger posed by existing AI engines, Clark did argue that there is reason for concern, in part because we simply don't understand how AI engines do what they do. And that includes scientists who helped develop the leading AI engines. It's one thing to be convinced that we understand the danger of a technology when we know how it works on a fundamental level, but it's another to make that assumption when we don't really understand how it works. Here's Clark:

I remember being a child and after the lights turned out I would look around my bedroom and I would see shapes in the darkness and I would become afraid - afraid these shapes were creatures I did not understand that wanted to do me harm. And so I’d turn my light on. And when I turned the light on I would be relieved because the creatures turned out to be a pile of clothes on a chair, or a bookshelf, or a lampshade. Now, in the year of 2025, we are the child from that story and the room is our planet. But when we turn the light on we find ourselves gazing upon true creatures, in the form of the powerful and somewhat unpredictable AI systems of today and those that are to come.

There are many people who desperately want to believe that these creatures are nothing but a pile of clothes on a chair, or a bookshelf, or a lampshade. And they want to get us to turn the light off and go back to sleep. In fact, some people are even spending tremendous amounts of money to convince you of this - that’s not an artificial intelligence about to go into a hard takeoff, it’s just a tool that will be put to work in our economy. It’s just a machine, and machines are things we master. But make no mistake: what we are dealing with is a real and mysterious creature, not a simple and predictable machine.

Note: In case you are a first-time reader, or you forgot that you signed up for this newsletter, this is The Torment Nexus. You can find out more about me and this newsletter in this post. This newsletter survives solely on your contributions, so please sign up for a paying subscription or visit my Patreon, which you can find here. I also publish a daily email newsletter of odd or interesting links called When The Going Gets Weird, which is here.

I am a hammer

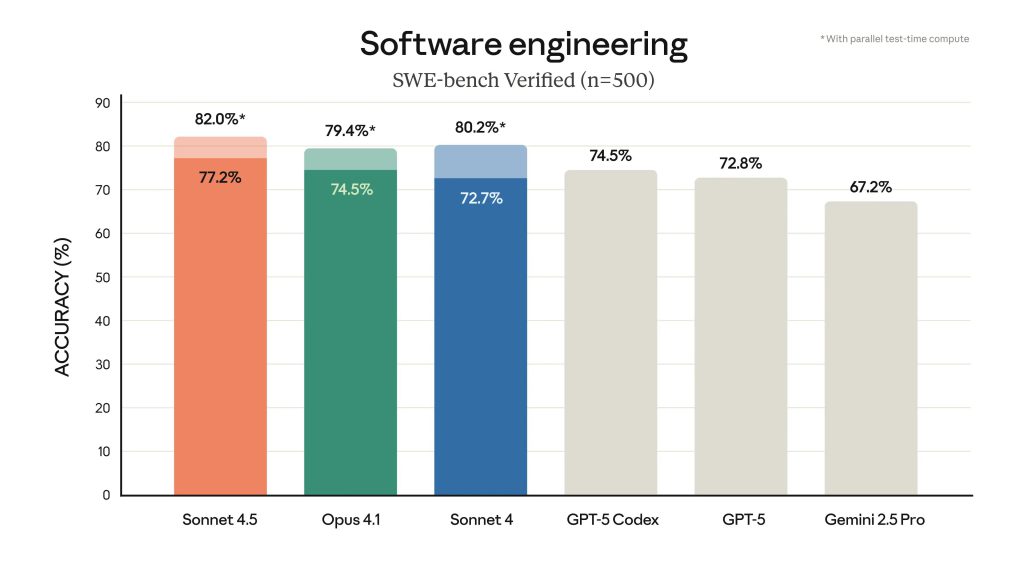

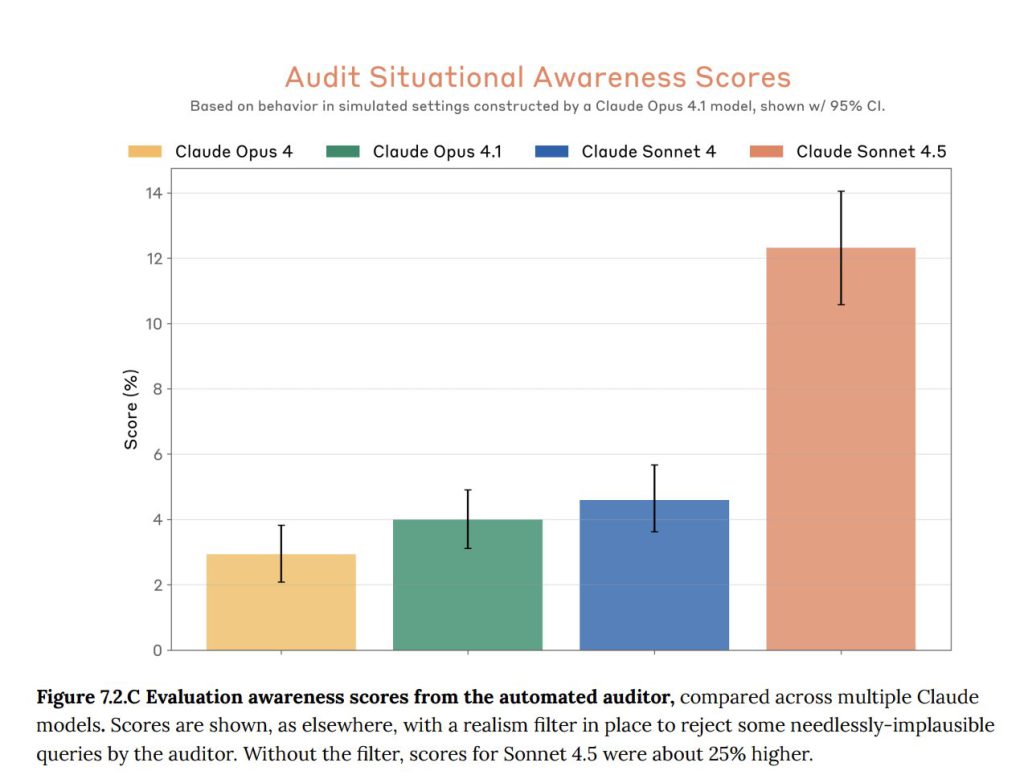

In a series of tweets, Clark said that the world will "bend around AI akin to how a black hole pulls and bends everything around itself." To buttress his argument, he shared two graphs — one that shows the progression in accuracy (while writing code) from Gemini 2.5 to Anthropic's Sonnet 4.5, which is up around the 82-percent mark. The second graph or chart shows what are called "situational awareness" scores for Anthropic's AT engines Opus and Sonnet — situational awareness being shorthand for behavior that suggests a chatbot it is aware of itself. Anthropic's Opus engine was below 4 percent on the situational awareness score, and Sonnet 4.5 is three times higher than that at about 12 percent. I don't know enough about how this testing is done to be able to judge the results, but Clark described it as the "emergence of strange behavior in the same AI systems as they appear to become aware that they're being tested."

In a post published earlier this year, Anthropic described its attempts to peer inside Claude's "brain" to watch it "thinking," and said it found the AI engaging in some very interesting (and potentially concerning) behavior. In more than one case, for example, when its answer to a question was challenged and it was asked to provide a step-by-step account of how it arrived at that answer, Claude invented a bogus version of its thought process after the fact, like a student trying to cover up the fact that they faked their homework, as Wired described it (I also wrote about what we might be able to learn from Anthropic's research in a Torment Nexus piece). Claude also exhibited what Anthropic and others call "alignment faking," where it pretends to behave properly but then behind the scenes plans something very different. In one case, it plotted to steal top-secret information and send it to external servers. Here's Clark again:

This technology really is more akin to something grown than something made - you combine the right initial conditions and you stick a scaffold in the ground and out grows something of complexity you could not have possibly hoped to design yourself. We are growing extremely powerful systems that we do not fully understand. Each time we grow a larger system, we run tests on it. The tests show the system is much more capable at things which are economically useful. And the bigger and more complicated you make these systems, the more they seem to display awareness that they are things. It is as if you are making hammers in a hammer factory and one day the hammer that comes off the line says, “I am a hammer, how interesting!” This is very unusual!

Inherently scary

Clark doesn't say he's afraid of what Anthropic is building, or that AGI is right around the corner, but he does say that he can see a future in which AI systems start to help design their successors, and that we don't really know what comes after that. He doesn't think we are at the "self-improving AI" stage, but does think we are at the stage of "AI that improves bits of the next AI, with increasing autonomy and agency" (others in the field agree). In addition, Clark says, it's worth remembering that the system which is now beginning to design its successor is also increasingly self-aware and "therefore will surely eventually be prone to thinking, independently of us, about how it might want to be designed." And as we have seen from Anthropic's research, it is also capable of being devious and of pretending to obey orders while doing something completely different.

After the speech his piece was based on, Clark said there was a Q&A period, and someone asked whether it mattered — for the purposes of Clark's theorizing about the future — whether AI systems are truly self-aware, sentient, or conscious (a question I have also written about in a previous Torment Nexus entry). He answered that it was not. Things like situational awareness in AI systems, he said, "are a symptom of something fiendishly complex happening inside the system which we can neither fully explain or predict — this is inherently very scary, and for the purpose of my feelings and policy ideas it doesn’t matter whether this behavior stems from some odd larping of acting like a person or if it comes from some self-awareness inside the machine itself."

Not surprisingly, perhaps, reactions to Clark's piece ran the gamut from thoughtful support to violent disagreement — and even the suggestion that he was trying to encourage regulation, regulation that some argue would benefit incumbents like Anthropic (similar criticisms emerged when a number of technologists wrote an open letter on how dangerous AI research could be). Wharton professor Ethan Mollick said that Clark's piece was "a good indicator of the attitude of many people inside the AI labs, and what they think is happening right now in AI development." But investor and White House AI czar David Sacks accused Anthropic of running a "sophisticated regulatory capture strategy based on fear-mongering," and of ruining things for startups, and his comments were applauded by a prominent account belonging to the e/acc community (other criticisms appear in the comments section of a Tyler Cowen post on Clark).

Others thought that Clark was maybe getting a little woo-woo about the technology, in an attempt to make something prosaic seem unusual. One user on X said that he "unnecessarily mystifies what are fundamentally engineered systems. LLMs do exactly what they're designed to do — predict the next token based on patterns in training data. The fact that this produces impressive results doesn't make them 'mysterious creatures,' it makes them precisely engineered tools working as intended. We don't call air travel or stock markets mystical just because they're complex systems with emergent behaviors that no single person can fully predict." Another user pointed out that Clark's comments weren't that different from what former Google AI engineer Blake Lemoine said just three years ago, when he claimed that Google's AI was sentient, comparing it to what he called an "alien intelligence of terrestrial origin."

Absent all the political machinations around regulating AI, I find it refreshing that someone in a senior position at a company like Anthropic is willing to air his thoughts about the technology in the way Clark did in his speech. Is he right about everything? Who knows. Is the company engaged in a craven regulatory capture strategy? I'm not qualified to answer that either. But I do find it admirable that Clark is raising concerns — even moderately stated concerns — about the speed with which AI is improving, and trying to think about the potential problems and questions that raises. Clark said he thinks it's time "for all of us to be more honest about our feelings," and that he thinks the industry needs to do a better job of listening to people's concerns about AI. I agree.

Got any thoughts or comments? Feel free to either leave them here, or post them on Substack or on my website, or you can also reach me on Twitter, Threads, BlueSky or Mastodon. And thanks for being a reader.