So what's so great about reading books?

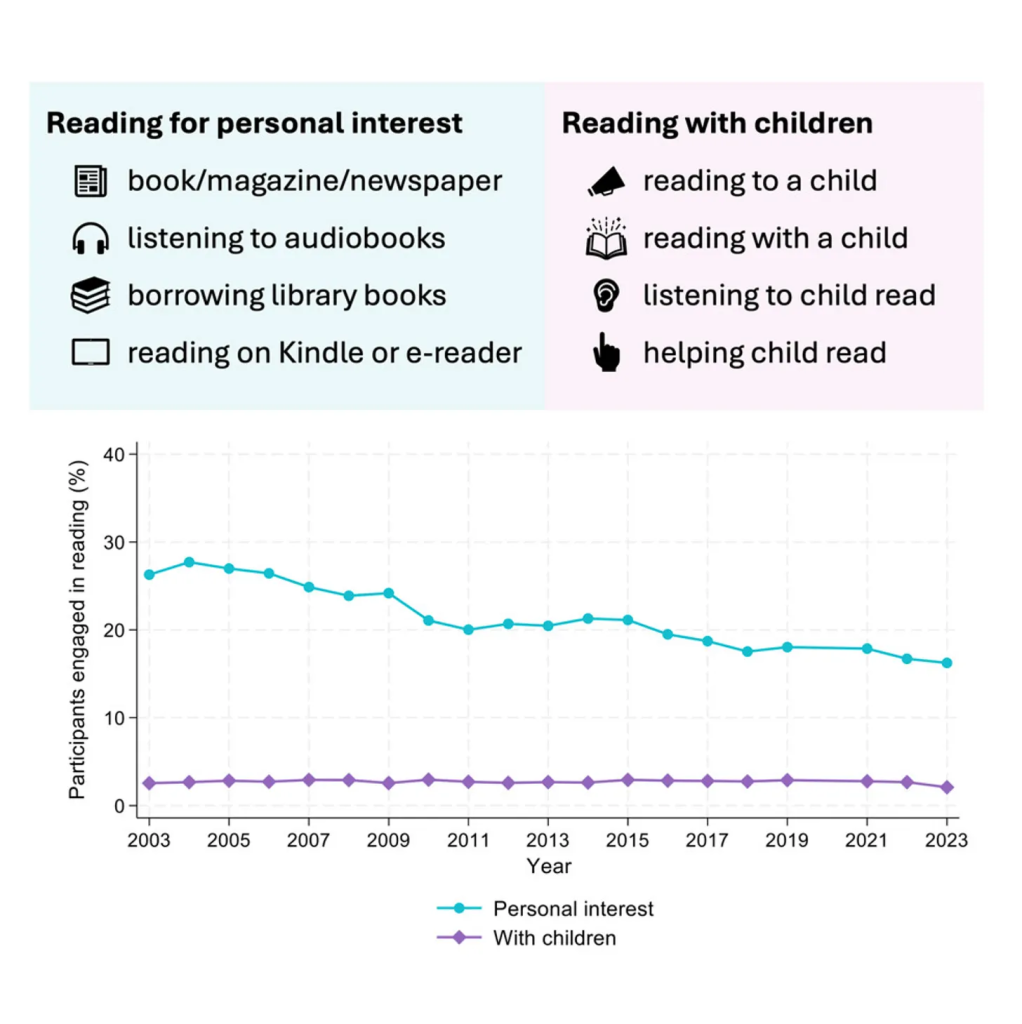

If you pay attention to the news at all, you may have seen a host of alarming headlines recently about how the number of Americans who say they read for pleasure has declined sharply over the past 20 years, from a peak of 28 percent in 2004 to 16 percent in 2023. That conclusion comes from a study done by a number of sociologists at the University of Florida, who looked at two decades worth of responses to a benchmark survey called the American Time Use Survey, which asks 10,000 randomly selected Americans every year how they spent the day prior to when they took the survey. The Florida researchers looked at how many people said they read "for personal interest," including books, magazines, newspapers, audiobooks, and e-readers (they also asked how many read a book with a child). It's worth noting that — like a lot of consumer surveys — the American Time Use Survey relies on people answering the questions truthfully, and because of the way it is conducted, it also relies on people who are a) willing to pick up the phone when it's an unknown number, and b) willing to answer a survey.

This dramatic decline in the numbers of people reading for pleasure is "deeply concerning," according to one of the study's co-authors, who called reading "a low-barrier, high-impact way to engage creatively and improve quality of life.” According to some neuroscientists, reading not only stimulates your brain in ways that other types of pleasure or activity don't, but it can also lower your blood pressure, reduce stress, help with sleeping, and even help you live longer. Other experts noted that in addition to the data cited by the Florida study, different studies have shown that there has been a generational decline in students reading for fun, which some argue is a result of social-media addiction, poor literacy training, overly busy after-school scheduling by parents, or some combination of all three. For others, this decline in reading is part of a disturbing trend that they believer represents the dawn of a "post-literate" society, a return to the largely oral cultures of primitive societies, and therefore pretty much represents the end of modern civilization as we know it.

Before I get any death threats from the publishing industry or from friends who are writers, I should note that the headline I chose for this essay is a least partly tongue-in-cheek. Obviously, reading books is a great thing to do, and everyone should do more of it whenever possible. In fact, you should probably stop reading this post and go read a book right now! But you don't have to convince me of the value of reading books: I grew up as a voracious reader, in a house full of other voracious readers, and I still enjoy reading books whenever I can — mostly non-fiction, but also some speculative fiction or sci-fi. Do I read as many books as I used to? No. Do I read as many as my mother, who would routinely check out 8 to 10 books a week from the library right up until she passed away at the age of 85? Not even close. But I do love books, and for a long time my idea of paradise was a musty old bookstore where the proprietor doesn't really care how long you spend there, or whether you even buy a book once you are done browsing.

At the same time, however, I don't think that reading books is the only useful thing we can do with our time, or the only way to encourage different ways of thinking or broaden our minds (or lower blood pressure and decrease stress), and I'm not sure I buy the argument that reading books is somehow orders of magnitude better than other kinds of reading. Also, whenever this topic comes up, I think the unspoken assumption is that people are reading War & Peace or The Brothers Karamazov, but let's face it — a huge portion of the book reading that is happening is probably more like the equivalent of potato chips for your brain: "beach reads" and fairy smut and poorly written detective novels and historical fiction that is more like the soap opera Days Of Our Lives than it is like War & Peace. I should point out that I don't have anything against this type of reading, even though I don't do it! But I don't think that we should talk about it like it's improving our brains on some deep, neuroscientific level.

A categorization problem

On a personal note, it's possible that beach reads and detective novels and so on don't appeal to me because I have something called aphantasia, which means that I am unable to form mental images. It's something that affects an estimated three or four percent of the population. If you ask most people to close their eyes and picture an apple, or a sunset, they can see some kind of image — in some cases a hazy one, or a grey shape, in others a full-colour image. At the far end of the spectrum are people who can close their eyes and see 3D movies (known as hyperphantasia). I see nothing but black! I can't even picture my mother's face, or my wife's face, or my childrens' faces. It's not that I don't know what they look like, it's just that there's nothing there when I try to picture them (others with this disorder include Mozilla developer Blake Ross, Pixar co-founder Ed Catmull, magician Penn Jillette, and author and YouTube star John Green).

Getting back to the topic at hand, I think it's important to note that the "decline in reading for pleasure" that everyone has written about based on the Florida study only includes books, magazines, and newspapers. It does include e-books (because at least some of this research stemmed from a concern that e-books would replace printed books, which they mostly haven't), but it doesn't include reading that occurs in other ways, including online. I don't know that many people under the age of 50 who read magazines or newspapers at all, let alone printed ones, so a survey that only collects that data is kind of missing the point, in my opinion. It's not that those people aren't reading, they are just doing it differently. Anne Helen Petersen, who writes a newsletter called Culture Study, noticed the same thing about the data, and here's how she described it:

The first thing I thought when I saw this data was that most people I know spend a lot of time reading the internet — but reading the internet is not considered “reading for pleasure,” even under the more expansive definition of reading a newspaper or magazine. What about reading Reddit? Or the “reading” we do on social media, or skimming the articles you see on the New York Times app, or reading an article that your friend sent to you at 9 pm over text? I’m thinking about how I would respond to an ask about how much “reading for pleasure” I did yesterday, and while I did spend 30 minutes reading a book before going to bed, I also spent a solid 45 minutes reading the captions and Q&As of various dahlia accounts, catching up on newsletters in the Substack app, and reading interviews with someone who was coming on the podcast.

I don’t want to argue over what is and isn’t reading or is or isn’t reading “for pleasure” so much as point out that the lines are incredibly blurred — and I don’t think the American Time Use Survey has figured out how to fully account for that reality. I don’t blame them! This shit is fuzzy! Technologically fuzzy, obviously, but it gets even more muddled given the freelancification of American labor. If I sell dahlia tubers very much on the side, but take pleasure in reading about dahlias, is reading about dahlias “pleasure” reading? Is reading a cookbook, or parsing an extended Reddit thread on a style of knitting, or getting super detailed in Dungeons & Dragons forums reading? Again, I don’t have answers, but I think it’s worth considering how this sort of slippage is convincing us that people read for pleasure far less than they do.

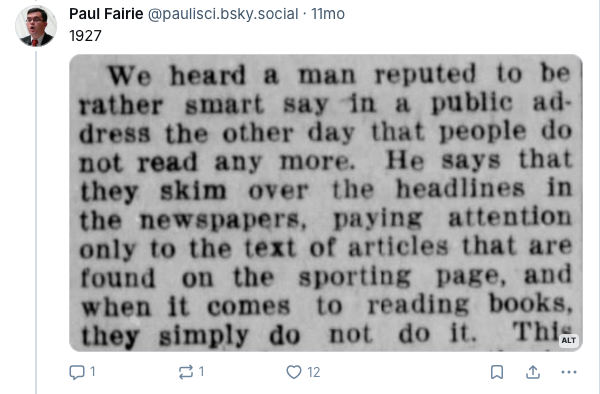

As for the fears that younger people are not developing the reading habit due to smartphones and TikTok and Discord and Snapchat, etc., some of those who specialize in this market remain untroubled. David Saylor is the creative director of the childrens' book publisher Scholastic, and helped get the Harry Potter series onto US bookshelves, and he says that by the time Harry Potter arrived, he had already been through several waves of predictions about how kids were no longer reading books. First it was television, and then it was video games — and before that it was radio and comic books. “I’m slightly jaded by these reports,” said Saylor, 65, “only because people are always predicting that kids are going to stop reading, and that the end of publishing is near.” Political scientist Paul Fairie had a Bluesky thread recently in which he shared press clippings from as far back as the 1920s complaining that people don't read any more.

There are many kinds of reading

According to author Maryanne Wolf, who often writes about the decline in literacy, research has found that the average American reads the equivalent of 34 gigabytes of information, or more than 100,000 words daily — in newspapers, magazines, books, games, text messages and social-media posts. That's about the length of a medium-sized book like To Kill a Mockingbird. However, Wolf doesn't think that any of this reading qualifies as actual reading, because it amounts to grazing rather than what she refers to as real "deep reading." The kind of reading people engage in now is “rarely continuous, sustained, or concentrated,” she says. Instead, it is “one spasmodic burst of activity after another.” Wolf says the fact that young people are reading all those words "means nothing” because it doesn't involve what she calls deep reading, which is synonymous with "critical thinking and empathy and the beauty of the reading act.”

Not to harp on the point I was trying to make earlier, but I would argue that the vast majority of reading for pleasure that happens in the US — and probably lots of other places — is not even close to this Platonic ideal of "deep reading." The Court of Thorns and Roses "fairy smut" series, which has sold more than 10 million copies, doesn't seem to me to be the kind of book that is synonymous with "critical thinking and the beauty of the reading act," although I will freely admit that I could be wrong. Nor do any of the Dan Brown novels, or literally anything that Stephen King has written (no offense Stephen). Does that make them bad? Not at all! They are incredibly fun to read. But I don't think they are light-years better on a neurological level than reading blog posts or email newsletters or even a Discord chat with a friend about the plot of a TV show.

Let me be clear: I am all for critical thinking, and empathy, and the beauty of the reading act! I think there should be more reading of that kind, and I wish that more people liked doing it, and I wish that more schools and parents would teach or encourage their kids to do it. And to be honest, I wish that more authors would write those kinds of books. But I am also in favour of reading of any kind, and I think that the human brain and our critical faculties and empathetic abilities can be enhanced and challenged and developed in a myriad of ways. The most creative reading and writing and imaginative exercise I've experienced in a long time took place during a Dungeons & Dragons session. Video games encourage problem solving in a variety of ways. A developer recently created a working version of the ChatGPT AI engine inside the game Minecraft. And Anne Helen Peterson mentions that a lot of learning occurs through podcasts.

I find it ironic that books have taken on this status as the most intellectual of all pursuits, given that when they first arrived, books were ridiculed and criticized as trash — cheap, easily plagiarized, garbage reading that not only made people stupider but in some cases condemned them to the fiery pit for eternity. Obviously, a big part of this was PR work on the part of the Catholic church, who didn't want people reading anything but the Bible, and the scribes who illustrated them. But underneath that was a truth: anyone can just write and publish a book! How are we to know whether what they are writing is reliable or not? The short answer is that we don't, which is why the London Review of Books was invented. But in a sense, books were the blogs and email newsletters and TikTok posts of their day – for every scientist using them to pass along actual knowledge, there were dozens of people writing about their favourite conspiracy theories.

If we look at the raw data, as shared by experts like Maryanne Wolf, it's pretty obvious that people are reading more than they probably ever have, in more places and for more reasons (book sales are also doing just fine according to the book publishing industry itself). The complaint appears to be that not enough of this reading falls into specific categories, or doesn't occur in specific ways, or isn't the type of reading that we like, or that people with college degrees like. Does this represent the beginning of the end, or the decline of Western civilization as we know it? I mean, maybe — but I highly doubt it.

Got any thoughts or comments? Feel free to either leave them here, or post them on Substack or on my website, or you can also reach me on Twitter, Threads, BlueSky or Mastodon. And thanks for being a reader.