Social media didn't start the fire, it just fans the flames

In a recent essay in Asterisk magazine entitled Scapegoating the Algorithm, Cambridge PhD and social scientist Dan Williams wrote that there seems to be a sense that the United States (and possibly other parts of the world) is going through an epistemic crisis, which he describes as a "breakdown in the country's collective capacity to agree on basic facts, distinguish truth from falsehood, and adhere to norms of rational debate." Williams goes on to say that this crisis encompasses everything from rampant political lies and general misinformation to outright conspiracy theories and "widespread belief in demonstrable falsehoods," (Pizzagate, etc.) as well as intense ideological polarization, and collapsing trust in the public institutions that we typically rely on to uphold basic standards of truth and a commitment to the scientific method, including universities, professional journalism, and public health agencies. He continues:

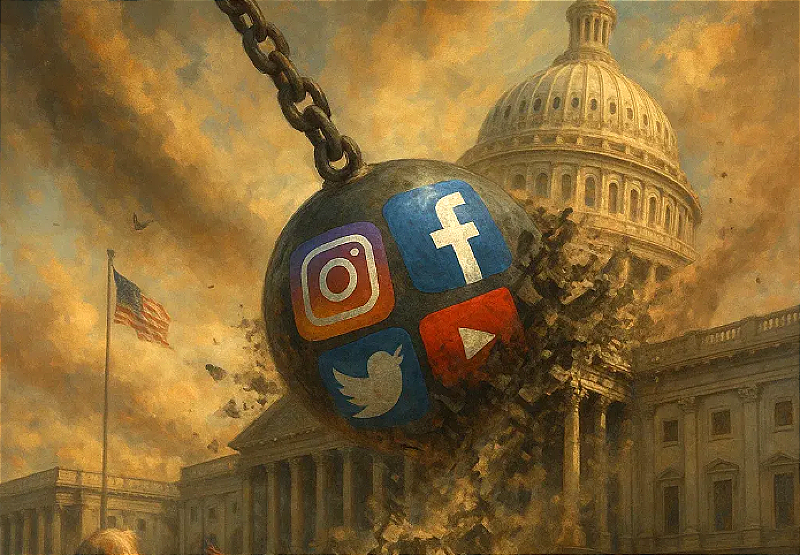

According to survey data, over 60% of Republicans believe Joe Biden’s presidency was illegitimate. 20% of Americans think vaccines are more dangerous than the diseases they prevent, and 36% think the specific risks of COVID-19 vaccines outweigh their benefits. What is driving these problems? One influential narrative blames social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter (now X), and YouTube. In the most extreme form of this narrative, such platforms are depicted as technological wrecking balls responsible for shattering the norms and institutions that kept citizens tethered to a shared reality, creating an informational Wild West dominated by viral falsehoods, bias-confirming echo chambers, and know-nothing punditry.

This is an appealing explanation, no question about it. Social media has plenty of flaws, and the ways that people use it can have many different negative – and in many cases unforeseen – consequences. But Williams argues that there are "compelling reasons to be skeptical that social media is a leading cause of America’s epistemic challenges." The wrecking-ball analogy, he says, exaggerates the extent and the novelty of these challenges, and overstates social media’s responsibility for them; it also overlooks deeper political and institutional problems that are reflected on social media, Williams argues. "The platforms are not harmless," he writes. "They may accelerate worrying trends, amplify fringe voices, and facilitate radicalization. However, the current balance of evidence suggests that the most consequential drivers of America’s large-scale epistemic challenges run much deeper than algorithms."

If you've been reading Torment Nexus for awhile now, you will be aware that this is an area of intense interest for me! One of the reasons I was nodding along to myself while I read Williams' piece is that I wrote something last year that tried to make a similar point, a post entitled Social media is a symptom, not a cause. At the time, I was trying to explain away a more specific version of the argument Williams is responding to – namely, the idea that social media and its ills, from ideological polarization to rampant disinformation, were responsible for the re-election of Donald Trump. Here's how I put it:

It's tempting to blame what happened on Tuesday night — the re-election of a former game-show host and inveterate liar with 34 felony counts and two impeachments as president of the United States — on social media in one form or another. Maybe you think that Musk used Twitter to platform white supremacists and swing voters to Trump, or that Facebook promoted Russian troll accounts posting AI-generated deepfakes of Kamala Harris eating cats and dogs, or that TikTok polarized voters using a combination of soft-core porn and Chinese-style indoctrination videos to change minds — and so on. In the end, that is too simple an explanation, just as blaming the New York Times' coverage of the race is too simple, or accusing more than half of the American electorate of being too stupid to see Trump for what he really is. They saw it, and they voted for him anyway.

When facts don't matter

I returned to this theme in a recent post that talked about the same kind of "epistemic crisis" that Williams described, a post I called "What happens when the facts don't matter?" That post was a response to a piece by Rachel Bedard, a doctor from Brooklyn, who wrote about the difficulty of fighting back against anti-science statements made by Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the US Secretary of Health – comments arguing that vaccines cause autism, for example, or that the germ theory of disease is inaccurate and illnesses are actually caused by a "miasma," or unclean air (Note: I am not making this up). Bedard argues that fighting these kinds of statements using facts, evidence, and an appeal to accepted standards of truth doesn't work, because most of these beliefs or statements are not based on evidence but are fundamentally emotional in nature.

In his essay, Williams makes the point that social media didn't invent problems such as political ignorance, conspiracy theories, propaganda, and bitter intergroup conflict, since these have "plagued the country throughout its history," including during the Civil War. He says the relative lack of polarization that occurred during the mid-twentieth century was a result of the two political parties’ "shared interests in upholding a system of racial apartheid in the South [which was] in turn, supported by widespread lies, racist myths, and censorship," including pseudo-scientific racism painting Black people as inferior. Nor is elite-driven disinformation something that Elon Musk invented – Henry Ford and William Randolph Hearst were famous for peddling it, and Williams notes that both the tobacco and oil industries have waged sophisticated disinformation campaigns in order to deny the harms caused by their products.

Note: In case you are a first-time reader, or you forgot that you signed up for this newsletter, this is The Torment Nexus. You can find out more about me and this newsletter in this post. This newsletter survives solely on your contributions, so please sign up for a paying subscription or visit my Patreon, which you can find here. I also publish a daily email newsletter of odd or interesting links called When The Going Gets Weird, which is here.

One other point that Williams makes that really resonated with me was that while it has become commonplace to blame social media for society's ills, much of the disinformation and conspiracy theory material that gets distributed via social media either originates with network television or is propagated by it, and polarization has increased the most in older populations, who are the least likely to use social media. As Williams notes:

It is easy to forget that most Americans still consume vast amounts of political information through traditional media channels, such as television, radio, and print. For example, Fox News remains by far the most prominent source of news for Republicans and Independents who lean Republican, with 57% saying they regularly get news from the cable network. The next most popular, ABC News, is at 27%. Among Democrats, traditional news sources are even more dominant. One landmark 2017 study led by Levi Boxell found that rates of polarization between 1996 and 2016 had increased the most among older Americans, the group least likely to use social media. [Also], polarization has moved in different directions in countries with similar rates of social media use. The US experienced the largest increase in a trend that began decades before the advent of social media, but half of the countries underwent a decrease in affective polarization during that time, including during the emergence of widespread social media use.

In my Torment Nexus post last November on social media and disinformation, I noted that social scientist Yochai Benkler — co-director of Harvard's Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society — has argued that the distribution of misinformation and partisan arguments by Fox News and other networks, which he describes as an evolution of conservative media that began with radio host Rush Limbaugh in the early 1990s, played a far bigger role in what happened in 2016 than anything that Twitter or Facebook did.

Demand drives supply

One of the other main points in Williams' piece centers around how and why people find disinformation. As he describes it, people "exercise significant agency over which information they encounter in the first place," meaning in many cases they go looking for things that they already agree with. This means that correlations between political attitudes and media use "often arise not because of media persuasion but because audiences are drawn to content that coheres with or rationalizes their pre-existing attitudes and worldviews." For that reason, a large proportion of the research into social media use and its impact on attitudes and behavior relies on correlation rather than showing causation, and can therefore be highly misleading (similar complaints have been made about Jonathan Haidt's theories about cellphones and the mental health of teens). As social scientist Sacha Altay has observed, people do not passively fall into disinformation rabbit holes, instead they “jump in and dig.”

This point also resonated with me, since I've argued that disinformation isn't a supply problem, it's a demand problem. By that I mean that the core of the problem lies not with Facebook and X and YouTube distributing disinformation, but with the elements of human nature that this caters to: a desire to be seen as more knowledgeable than others, for example, in the sense that one possesses a key to some kind of secret information others are unaware of. QAnon is a recent archetype, and secret societies like Scientology and fraternities like the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn also played on this (not to mention virtually every established religion). In addition to the feeling of having secret knowledge, sociologists say one of the biggest factors in conspiracy-theory belief is the sense of community and togetherness that comes with it.

In my post on social media last November, I mentioned an interview I did with Carl Miller, research director at the Centre for the Analysis of Social Media at Demos in the UK, who told me that most people have “fairly naive ideas" about how disinformation works. People imagine that bad actors spread convincing yet untrue images about the world in order to get people to change their minds on important social topics, Miller said, but most influence operations are designed not to spread misinformation but rather to “agree with people’s worldviews, flatter them, confirm them, and then try to harness that." In other words, misinformation only works if there is an existing belief to play off. It doesn't create beliefs so much as it reinforces them. As I wrote then:

In a 2022 piece for the Carnegie Endowment, Gavin Wilde pointed out that researchers at Cambridge University recently concluded that in many cases, people find that ignorance and self-deception have what psychologists and sociologists like to call “greater subjective utility than an accurate understanding of the world.” In other words, for a variety of reasons, people often prefer things that aren't true — even if they are presented with the actual facts. This is fairly depressing, but it suggests that focusing solely on the supply of inaccurate information is a mistake. It also suggests that what people describe as a marketplace of ideas is often just a “market for rationalizations, a social structure in which agents compete to produce justifications of widely desired beliefs in exchange for money and social rewards.”

In effect, social media platforms are mostly echo chambers that reflect something that has already emerged elsewhere, the truth of which already has many people convinced. Social media didn't start the fire, in other words – it just fans the flames. So why do we believe that social media has caused the decline of Western civilization, despite an almost complete lack of evidence to support this belief? For the same reason many choose to believe that vaccines cause autism, or that Hillary Clinton ran a child-abuse cult out of the basement of a pizza parlor: because the belief is more interesting than the truth, and also because it gives us someone or something to blame for the ills we see around us. It makes solving complex social problems seem as simple as getting rid of Twitter.

Got any thoughts or comments? Feel free to either leave them here, or post them on Substack or on my website, or you can also reach me on Twitter, Threads, BlueSky or Mastodon. And thanks for being a reader.