The Google link economy is dying and it's not coming back

Ever since Google climbed onto the artificial intelligence bandwagon last year by announcing that AI results would start appearing at the top of search pages, there has been a suspicion that by using AI to provide answers, Google would inevitably wind up displacing websites and media companies whose businesses depend on doing exactly that, and that by doing so it would ultimately kill off the search-based link/advertising economy. There have been hints that this is happening for some time now — including a comment from Apple exec Eddy Cue, during one of Google's antitrust trials in May, that search traffic through Apple's Safari browser had declined in April for the first time in the history of the company, which he blamed on AI agents taking over from search. Last month, Cloudflare CEO Matthew Prince said that ten years ago, Google's ratio of pages crawled to visitors referred was 2:1. Today, he said, it's about 18:1, implying that the amount of users who click on those blue links has declined significantly.

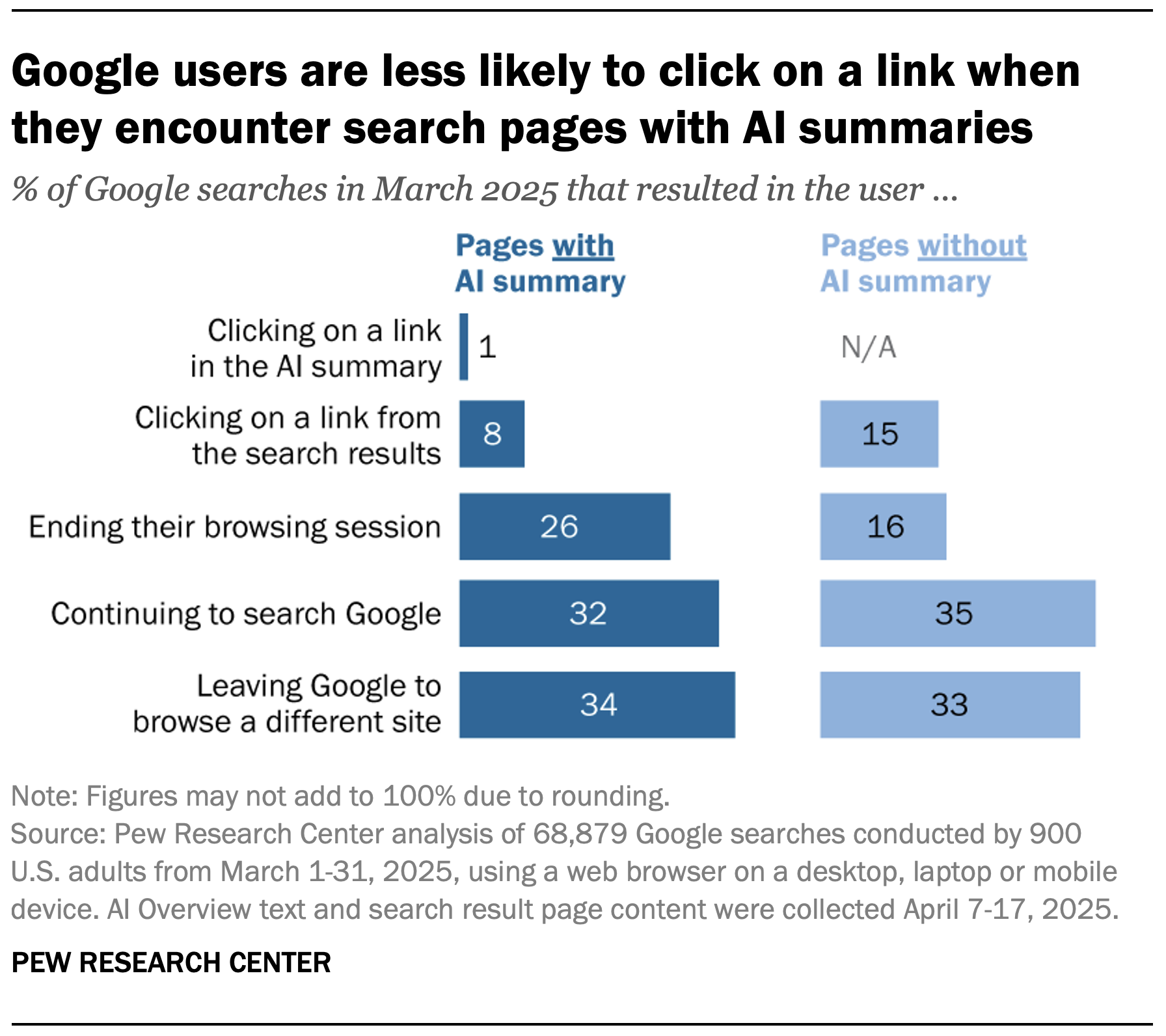

Now there is more evidence that AI is contributing to the decline of the link: as Ars Technica reported, new research from the Pew Research Center appears to show a conclusive — and significant — drop in users clicking on links in search results. The study looked at data from 900 users of the Ipsos KnowledgePanel whose behavior and activity was collected in March 2025, and the analysis showed that among the test group, users were much less likely to click on search results when the page included an AI Overview. Pew reported that searches without an AI answer had an average click rate of 15 percent, while the average click-through rate on results with AI overviews included was in the range of 8 percent, or almost 50 percent lower. Google often claims that people click on the links to original sources that it includes with some of its AI overviews, but Pew found that just 1 percent of AI overviews resulted in a click on a source link.

In a statement sent to multiple news outlets who reported on the research, Google maintained that the Pew study was based on a "flawed methodology and skewed queryset that is not representative of search traffic," and that it "consistently directs billions of clicks to websites daily and [we] have not observed significant drops in aggregate web traffic as is being suggested." According to Casey Newton's Platformer newsletter, Google noted that queries that produce AI overviews in results "tend to be the sort of thing that people wouldn't have clicked on anyway," such as queries that begin with "who," "what," "when," or "why" — the sort of simple questions that Google once previously answered on the page via other means, and which also probably didn't generate a lot of traffic to publishers. However, Newton noted that "we're seeing more studies like this, and Google has yet to answer with any raw data of its own."

Note: In case you are a first-time reader, or you forgot that you signed up for this newsletter, this is The Torment Nexus. You can find out more about me and this newsletter in this post. This newsletter survives solely on your contributions, so please sign up for a paying subscription or visit my Patreon, which you can find here. I also publish a daily email newsletter of odd or interesting links called When The Going Gets Weird, which is here.

The symbiosis is no more

Although it may not be due to Google's AI results specifically, there have been other signs that all is not well with the link-based economy, and the growth of AI is the chief culprit: Business Insider, which rode search advertising to great heights in the mid-2000s — culminating in an acquisition by German media giant Axel Springer in 2015 for close to $400 million — recently announced that it was laying off 21 percent of its staff, and CEO Barbara Peng cited shrinking search traffic due to AI. Others have also been cutting, even though the media industry has already spent years enduring round after round of cuts. Fortune magazine recently announced that it was cutting 10 percent of its staff, and others have also been on the chopping block. The blame in most cases has been placed on the decline of search traffic (although as Newton notes, media companies often blame others for flaws in their business models or an inability to adapt).

The symbiotic relationship between Google and publishers that has existed for most of the past quarter century or so has been very good for Google and (mostly) good for publishers — the ones that have been able to adapt — but the arrival of AI threatens to dismantle that relationship, possibly forever. But it's not like Google has somehow chosen to do this to publishers and the link economy out of spite, or because it wants to throw its weight and power around, and doesn't care if publishers take a hit. It doesn't really have a choice: AI is eating into the publishing and search industries whether Google likes it or not, and if it doesn't provide answers to the questions people search for, whether through AI or some other means, then ChatGPT or Claude or Perplexity or some Chinese AI agent will do it, and in the process they will eat Google's multibillion-dollar lunch. So it is getting rid of those blue links as quickly as it possibly can. (I wrote about the decline of the open web in a recent edition of Torment Nexus).

Longtime media-industry watcher Ben Thompson wrote an in-depth analysis of the evolution of publishing and the rise of the link economy, and the risks for the future, in a recent edition of his Stratechery newsletter, going all the way back to the printing press and discussing how printing and publishing helped to build (and destroy) nations, before being commoditized and eventually disintermediated by the internet. As he describes it:

I have long thought that what happened to content was a harbinger for what would happen to industries of all types. Content was trivially digitized, which means the forces of digital particularly zero marginal cost reproduction and distribution manifested in content industries first, but were by no means limited to them. That meant that if you could understand how the Internet impacted publishing — newspapers, books, magazines, music, movies, etc. — you might have a template for what would happen to other industries as they themselves digitized. AI is the apotheosis of this story and, in retrospect, it's a story the development of which stretches back not just to the creation of the Internet, but hundreds of years prior and the invention of the printing press. Or, if you really want to get crazy, to the evolution of humanity itself.

One thing that is hard for journalists and publishers to grapple with is that the decline we have seen — first with the web and Google, and then as a result of apps and social networks like Facebook and TikTok — is just the most recent skirmish in a long, drawn-out war to keep a firm grip on the attention of readers and users. Media companies and journalists like to blame Google, or Facebook, or Craigslist, but if you zoom out enough the print publishing industry has been losing market share ever since radio was invented. That decline picked up speed after television became the dominant medium and accelerated even further in the late 1990s, as the internet and the consumer web began to gain increasing traction with audiences. The falloff in readers and advertising revenue from the rise of the internet and social media and web publishing is really just a smallish blip at the end of a much longer and protracted slide.

Avoid the golden handcuffs

As noted earlier, publishers who were willing to adapt have had not a bad time since Google took over as the front page of the internet — not as good as some of them had back in the good old days when they had local monopolies, but not bad. Unfortunately, getting hitched to Google and its blue links came with some pretty large golden handcuffs, and even media companies that didn't want to be beholden to the big G have had little or no success replacing search advertising with anything else — except for a handful of players that already had existing subscription-based businesses, such as the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, the Financial Times, etc. Some have managed to bolt on a subscription business (The Guardian's donation-based model comes to mind) — but successful transitions like that are few and far between. And now, Google is taking all of that away. The handcuffs are gone, but unfortunately so is the gold, and media companies are flailing and in many cases sinking.

Not content in the role of the villain in this morality play, Google has come up with a couple of new plans to smooth over its publisher relationships. The first is something called Offerwall, which allows publishers to offer other ways to access their content apart from just ads – such as micropayments, taking surveys, etc. This seems like a Hail Mary pass at best, and the likelihood of anyone turning it into something significant to their business seems vanishingly small. The second plan, according to Bloomberg, involves payments to publishers for results that show up in AI-powered search results. The program is just a rumor at this point, but if Google's history with this kind of thing is anything to go by, it will make a difference for a tiny handful of companies and publishers, and for others it will be just another mirage, promising water and palm trees and delivering nothing but sand. Also, accepting these offerings delays the inevitable, and makes it harder than ever for publishers to detach themselves.

So what other options are there? Just get paid by AI companies so they can crawl your content, through a program like Cloudflare recently announced? I expect this will amount to pennies, and as Ben Thompson suggests, the rise of AI-generated content is likely to create an entirely new class of providers and content companies, leaving existing publishers to pick up the scraps and leftovers. So should publishers – and that includes individual content creators – just go gentle into that good night? No. Thompson argues that the way to succeed is to focus not on an audience's clicks or ad views, but on creating a community – something that I have been passionate about since my earliest days as an online journalist, and one of the reasons I was so eager to adopt social media, and in fact tried to get the newspaper I worked for to create its own online Reddit-style community in the mid-2000s. Here's how Ben puts it:

So, are existing publishers doomed? Well by-and-large yes, but that’s because they have been doomed for a long time. People using AI instead of Google — or Google using AI to provide answers above links — make the long-term outlook for advertising-based publishers worse, but that’s an acceleration of a demise that has been in motion for a long time. To that end, the answer for publishers in the age of AI is no different than it was in the age of Aggregators: build a direct connection with readers. This, by extension, means business models that maximize revenue per user, which is to say subscriptions (the business model that undergirds this site, and an increasing number of others). What I think is intriguing, however, is the possibility to go back to the future. Once upon a time publishing made countries; the new opportunity for publishing is to make communities.

Thompson goes on to argue that the digital environment is customized to the individual, and as AI agents and large-language models consume everything, the "hunger for something shared is going to increase." In short, he says, there is human desire for community (which I think helps explain why Reddit, one of the earliest online communities, has not only survived but arguably become even more important, as New York magazine recently reported). That suggests that for creators who are open to the possibility, content of any kind – essays, podcasts, videos – can help generate or attract a community, and that this can result in an economic benefit for the creator. This was the core thesis of Kevin Kelly's "10,000 true fans" model, which he wrote about in 2008. Can this model be used for evil as well as good? Obviously yes, and there are numerous examples (Alex Jones and his empire comes to mind). But the same model can be used by those with more enlightened principles as well. There is more to life than Google.

Got any thoughts or comments? Feel free to either leave them here, or post them on Substack or on my website, or you can also reach me on Twitter, Threads, BlueSky or Mastodon. And thanks for being a reader.