The Meta antitrust case started out weak and got worse

The Federal Trade Commission's antitrust case against Meta was dismissed in its entirety on February 18th by Judge James Boasberg of the District Court for the District of Columbia. Just to recap for those who haven't been following every bump and hurdle of this five-year case, the FTC first charged Meta with having an illegal monopoly and maintaining that monopoly via anti-competitive behavior in December of 2020 (I wrote about the lawsuit for the Columbia Journalism Review, where I was the chief digital writer at the time). The case was rejected the following year by the very same Judge Boasberg because he said the FTC had failed to prove that Meta had a monopoly over a distinct market (I wrote about that for CJR too). However, the judge gave the FTC a chance to re-file the case provided it came up with more evidence of a monopoly, so it tried to do so – and on Tuesday, the judge threw that case out just like he did the previous one, saying the evidence provided failed to prove the FTC's case. From Politico:

Meta’s acquisition of Instagram and WhatsApp did not create an illegal social media monopoly, a federal judge ruled Tuesday, a decision that solidifies the future of the $1.5 trillion tech giant. Judge James Boasberg in Washington rejected the Federal Trade Commission’s claim that Facebook’s parent company monopolized the “personal social networking” market for connecting with friends and family. "As it has forecast in prior Opinions over the years, the FTC has an uphill battle to establish the contours of any separate PSN market and Defendant’s monopoly therein," Boasberg wrote. "The Court ultimately concludes that the agency has not carried its burden: Meta holds no monopoly in the relevant market."

One of the key points in the FTC case – which was originally joined by a similar lawsuit filed on behalf of 46 states, although the latter was also thrown out by Boasberg in 2021 – was that because of its allegedly monopolistic position in the personal social-networking market, the company should not have been allowed to acquire either Instagram (which it bought in 2012 for $1 billion) or WhatsApp, which it acquired in 2014 for $22 billion. According to the FTC, Instagram cemented Meta's dominance over photo-related social networking, and WhatsApp entrenched its position in person-to-person text messaging – especially in non-US countries, since WhatsApp is free and when it was acquired many countries charged users for sending text messages. Meta, not surprisingly, pointed out that both acquisitions were approved by the Federal Trade Commission at the time they were done, but the FTC was unmoved. Here's how the New York Times summarized the case when it was first launched in 2020:

“Facebook, the prosecutors said Wednesday, should break off Instagram and WhatsApp, and they said new restrictions should apply to the company on future deals. Those are some of the most severe penalties regulators can demand. Facebook said it planned to vigorously defend itself against the accusations. For nearly a decade, Facebook has used its dominance and monopoly power to crush smaller rivals and snuff out competition, all at the expense of everyday users,” said Attorney General Letitia James of New York, a Democrat who led the multistate investigation into the company in parallel with the federal agency, which is overseen by a Republican.

At the time the Meta lawsuit was re-filed, it seemed as though both Meta and Google might be up against some significant legal challenges – Google was in the midst of a lawsuit from the Department of Justice alleging that it maintained an illegal monopoly in the online advertising market, as well as another separate DoJ lawsuit alleging that it also had an illegal monopoly in the online search market (the federal government won the first in April of this year – although Google says it plans to appeal – and the second ended in a weak decision that I argued was the correct one). These cases were inspired by FTC chairperson Lina Khan's arguments about how the nature of US antitrust needed to change, and by a 450-page report from the House Judiciary Committee detailing concerns about tech companies. Khan and others in the Trump administration believed that the tech giants had escaped antitrust justice, in part because modern antitrust law was not equipped to deal with monopolies in the age of the internet.

Note: In case you are a first-time reader, or you forgot that you signed up for this newsletter, this is The Torment Nexus. You can find out more about me and this newsletter in this post. This newsletter survives solely on your contributions, so please sign up for a paying subscription or visit my Patreon, which you can find here. I also publish a daily email newsletter of odd or interesting links called When The Going Gets Weird, which is here.

Heraclitus and the river

One of the most difficult parts of the antitrust case against Meta doesn't have anything to do with the nuances of modern antitrust, and isn't even really about how to define the "personal social networking" market, although that was the source of much dissent and debate from both sides of the case. In the end, it had to do with the speed with which technology changes – even the fairly mundane variety, like Meta and Instagram and their algorithmic photo and video-sharing. The original launch of the antitrust lawsuit might seem like it wasn't that long ago, but in technology terms, 2020 might as well be a decade ago. When that purchase was made, TikTok was only two years old, and had yet to destabilize the entire social-networking market. Facebook's market value was only $700 billion or so at the time (it's now greater than $1.5 trillion). I think Judge Boasberg described this problem well in the introduction to his decision:

The Greek philosopher Heraclitus posited that no man can ever step into the same river twice. In the online world of social media, the current runs fast, too. The landscape that existed only five years ago when the Federal Trade Commission brought this antitrust suit has changed markedly. While it once might have made sense to partition apps into separate markets of social networking and social media, that wall has since broken down. Like Heraclitus’s river, the rapids of social media rush along so fast that the Court has never even stepped into the same case twice. The Court’s two Opinions on motions to dismiss did not even mention the word “TikTok.” Today, that app holds center stage as Meta’s fiercest rival.

As Casey Newton noted in his Platformer newsletter, this point was driven home by a simple experiment that Meta conducted in which a University of Chicago professor tracked the behavior of 6,000 users who were offered payment if they stopped using Facebook or Instagram. Most participants were happy to stop using Meta products for a few dollars, and their usage fell by about two-thirds. The top destination for those shut out of Facebook and Instagram was YouTube, and the second choice was whichever Meta app they weren’t being paid to avoid. Third was TikTok. Judge Boasberg apparently found the study compelling. "This experiment, which in the Court’s judgment offers the single best evidence of what consumers consider alternatives to Meta’s apps, tells a clear and consistent story,” he wrote. “When using Facebook and Instagram becomes more costly, users turn to TikTok, YouTube, and Snapchat, with no other app notably standing out.”

Even at the time the FTC's case against Meta was re-filed, it was obvious to many that TikTok should have been included as a competitor for both Facebook and especially Instagram, and it was even more obvious that YouTube should have been included as well. The fact that the FTC didn't include either one made the entire case seem shaky at best. Not everyone agreed: Tim Wu, the Columbia law professor who coined the term "net neutrality" argued in an op-ed for the New York Times in 2020 that Meta's anti-competitive strategy of acquiring Instagram and WhatsApp was the same as the one employed by John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil in the 1880s, behavior that led directly to the creation of the Sherman Act, the foundation of modern US antitrust law. But in the end, it came down to whether Meta had a monopoly over a discrete market, and Boasberg said no. Here's Newton's summary of how the judge approached it:

Boasberg observed, accurately, that the friends-and-family era of the “social graph” is over, having been replaced with what Meta grimly calls “unconnected content” — posts from accounts that you may or may not follow, and have been chosen for you by a recommendation algorithm. Boasberg notes that this is a natural byproduct of people choosing to share fewer posts of their own, forcing companies like Meta to find alternatives. The social graph no longer has the power it once did. “Longtime users’ friend lists have … become an often-outdated archive of people they once knew,” Boasberg writes. “A casual friend from college, a long-ago friend from summer camp, some guy they met at a party once. Posts from friends have therefore grown less interesting.”

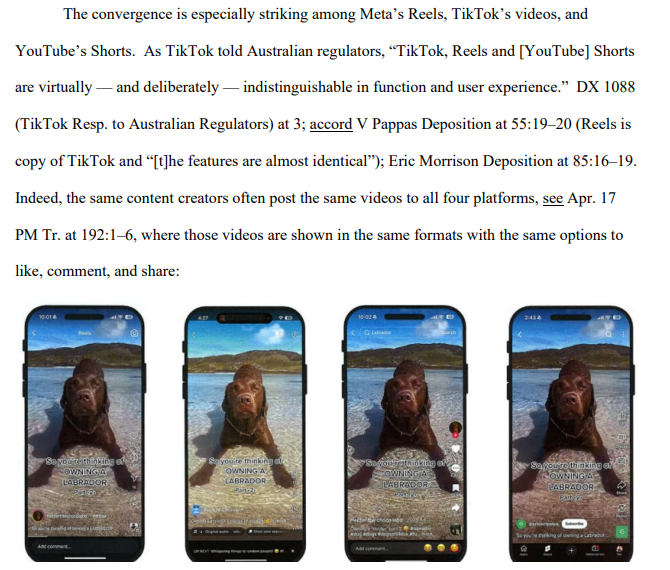

The TikTok tsunami

For someone who reportedly doesn't use any social media, Judge Boasberg did a pretty good job of describing what happened after the arrival of TikTok – how the completely algorithm-driven nature of that app put pressure on Meta to do the same with both Facebook and Instagram, decreasing the amount of real estate given to updates from people's friends and increasing the number of posts from complete strangers. Instagram added Reels, which were essentially an attempt to copy TikTok's viral posts, and they quickly got crossposted to Facebook. As Boasberg notes, that and other trends "transformed Facebook and Instagram into the apps that exist today, ones that primarily show users short unconnected videos recommended by algorithms. Both apps are pushing still further in that direction. In just the last two years, the share of time on Facebook that Americans spent viewing friends’ content fell by almost a quarter; the share of time they spent watching Reels more than doubled."

None of this, of course, means that Meta didn't either have a monopoly in the past, and perhaps even when the company acquired Instagram and WhatsApp – although as Boasberg points out that under US antitrust law, simply having a monopoly in a certain market segment is not enough; a monopolist must have achieved that position through anticompetitive means and/or maintain its monopoly through anticompetitive means. In any case, Boasberg says, the question of whether Meta had an illegal monopoly when it acquired them is moot, because in order to find the social network guilty, the law requires that Meta be proven to be engaged in anticompetitive behavior now.

Throughout this case, the Court has held that the agency must prove that Meta is violating the law now. In its post-trial brief, the FTC nonetheless tries another angle, arguing that if Meta broke the law in the past and this violation is still harming competition, then the agency may seek an injunction to redress the lingering harm. That might be a sensible statutory scheme, but it is not the one that Congress passed. The FTC’s authority to seek injunctions comes from Section 13(b) of the FTC Act: “Whenever the Commission has reason to believe that any . . . corporation is violating, or is about to violate, any provision of law enforced by the Federal Trade Commission."

There is one potential silver lining for those who feel that Meta is a terrible company that deserves to be reined in, and Casey Newton outlines it in his newsletter: namely, that the FTC's case may not have succeeded but – much like the antitrust case against Microsoft in its day – the regulatory pressure may have prevented Meta from making other big acquisitions, including some in the area of AI, where it has been behind the curve for some time (to the point where it had to open source its large-language model, which is typically something that only the underdog in a market does). As Newton puts it, "for the past five years, Meta has struggled to acquire any other company in its space. And what happened during that time? Competition! ChatGPT launched in 2022 and turned OpenAI into a juggernaut." Small comfort perhaps, but in some ways the concerns about social networking monopolies seem almost quaint now.

Got any thoughts or comments? Feel free to either leave them here, or post them on Substack or on my website, or you can also reach me on Twitter, Threads, BlueSky or Mastodon. And thanks for being a reader.