Welcome to The Torment Nexus

Hi everyone! My name is Mathew Ingram, and this is a newsletter called "The Torment Nexus."

Hi everyone! Mathew Ingram here. Just wanted to let you all know that I'm launching a newsletter about technology and society called "The Torment Nexus." I know that none of you were expecting to get this in your inbox, and I apologize for springing it on you like this without warning, but I thought that some of you who know me and my previous work might be interested in subscribing to it.

I was recently laid off from my job as chief digital writer for the Columbia Journalism Review, where I have been writing since 2017 about Twitter and Facebook and Google and every other kind of social media, so I decided to run this up the old flagpole and see if anyone salutes 😄 If I am wrong, and you aren't interested, please feel free to unsubscribe (I won't be offended, I promise!) or reply to this and I will take your name off the list. For those of you who are interested, please read on! And feel free to share this and other posts with anyone you think might have an interest in these kinds of topics.

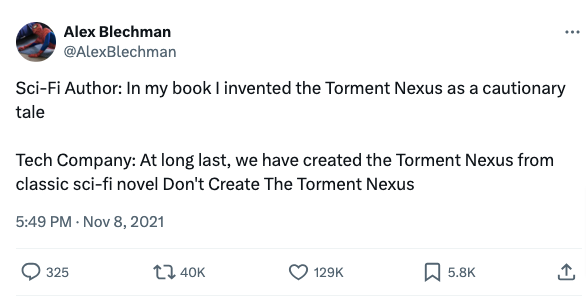

In case the name Torment Nexus doesn't ring a bell, it comes from a hilarious meme that Alex Blechman—a writer for The Onion—came up with awhile back, and I think it sums up so much about where we are right now in terms of our relationship with technology. Here Alex's original tweet:

Another popular meme along similar lines shows Jeffrey Goldblum's character in the movie "Jurassic Park" telling someone: “Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should.”

This doesn't mean I'm anti-technology, by any means! I've been using digital technology of various kinds and (for the most part) enjoying it since I got my first PC — an Atari 1040ST, with a graphic interface and MIDI support — in the mid-1980s. As for the web, it is easily one of the most fascinating and life-changing technologies I've ever come across, and I've been more or less addicted to it since Marc Andreessen invented the first web browser. Things like Google Earth continue to amaze me. I've also been an enthusiastic user of every social-media app from Twitter and Tumblr to Facebook and Google+ (RIP.)

For those who don't know me, I've also been writing about technology since Apple was $5 a share and headed for bankruptcy (or so everyone said), and Research In Motion's Blackberry was the height of mobile tech. I wrote about Google's IPO, and the downfall of Nortel Networks. I was one of the first social-media editors at a major newspaper in North America (as far as I know), where I helped launch and moderate reader comments, used Facebook and live-blogging to help cover the election of Barack Obama, and started a wiki aimed at crowdsourcing readers' thoughts about politics (RIP.) I also co-founded a conference called Mesh, where we talked with experts about things like blogs and YouTube, and why Craigslist looked so terrible but was worth billions.

In 2010, I left the newspaper to join a San Francisco-based blog network called Gigaom, founded by my friend Om Malik. I worked there for five years, writing about brand new things like Twitter and Instagram and analyzing important questions like whether bloggers are journalists (I also wrote about how Jack Dorsey might be the new Steve Jobs, and I apologize for that.) When Gigaom ran out of money, a bunch of the writers joined Fortune magazine, where I wrote about Twitter and important questions like whether we should refer to Donald Trump as a liar, a discussion that seems so quaint now it might as well have been about whether cars should replace the horse-drawn carriage. After a few years at Fortune I joined the Columbia Journalism Review.

Despite my long history as a fan and enthusiastic user of technology — or possibly because of it — I would be the first to admit that some technology has flaws, which is not surprising, since it is created by human beings. There are aspects of technology that are fundamentally hostile both to users and (arguably) to society itself, from printers that stop working if you try to use discount ink to social networks that empower a genocide, as Facebook arguably did in Myanmar. A lot of technology—with AI being just the latest example—seems to be driven by an attitude of "why don't we try this and see what happens," (or "move fast and break things," as Mark Zuckerberg famously put it.) This is great, unless what you wind up breaking is democracy, or our ability to understand the world.

What I'm hoping to do with this newsletter is to bring a critical eye and some historical context to discussions of how technology impacts both individual users and society as a whole. If the tech is being used in ways that are helpful, I will say so. If I think it—or its creators—are being misunderstood, then I will say that. And if the technology is being created or used in negative ways, or there are aspects people should be wary of, I will point that out too. It's even possible that in some cases, all three of the above things will be true. If you disagree or think that my perspective is wrong, I hope you will let me know!

I'm hoping to write an essay-length piece (800-1000 words or so) at least every week, and hopefully at some point twice a week, but since this is a new venture I am going to try to remain flexible, and I hope that you will too. And of course, I will include some hilarious tweets and/or memes, as I do in my other newsletter, When The Going Gets Weird. By way of an introductory piece, here's an abridged version of something that I wrote for the Columbia Journalism Review, looking at how things have changed — or have not changed — since I started writing there in 2017 (my apologies to those who have already seen it.)

So long, and thanks for all the fish

In case the headline doesn’t make any sense, it comes from a Douglas Adams book, in which he describes how all the dolphins suddenly vanished from the Earth, leaving behind the message: “So long, and thanks for all the fish!” As I reflected on the last seven years or so of writing about the intersection of media and technology, I started to think about what (if anything) has changed since my first CJR piece was published, in October 2017—an essay headlined “The 140-character president,” about Donald Trump’s obsession with what was then known as Twitter.

Obviously, some things have changed quite a bit. Trump is no longer president (although he is trying hard to regain that position), and Twitter—now known as X—is owned by Elon Musk, the billionaire who also owns Tesla and SpaceX. Much has been written (by me and just about everyone else) about Musk’s problem-plagued acquisition of the platform, and the changes he has made to it; it is reportedly hemorrhaging money and scrambling for both users and revenue. None of this is particularly new—the old Twitter under cofounders Jack Dorsey and Ev Williams also seemed to be continually scrambling for money and users. The reasons have changed, however: Musk, who maintains that his guiding principle is to enable free speech, has enabled many of the worst kinds of speech, including white supremacy, racism, and misogyny. This has (not surprisingly) led to an exodus of both users and advertisers.

These days, one popular conspiracy theory is that Musk is a Russian stooge who is trying to help Trump get reelected, a theory based in part on rumors about Russian troops in Ukraine using Musk’s Starlink for internet access and whispers that Putin-adjacent sources helped fund the purchase of Twitter. (The evidence for this is circumstantial—at best.) Russia’s involvement in a variety of nefarious projects (or rumors thereof) has been a consistent theme since I started writing for CJR. An early taste of that came in November 2017, when I traveled to Washington and sat in on a series of congressional hearings looking into whether Meta (then known as Facebook), Google, and Twitter had allowed Russia and Russian-aligned agents to use their services as the foundation of a gigantic disinformation campaign. Did this happen? Yes, at least in a limited way. Did it affect the outcome of the 2016 election? Opinion remains divided, but some of the smartest people in the field say no, it likely did not.

A related topic that has resurfaced again and again is whether misinformation and disinformation (Russian or otherwise) is a scourge that should be eradicated—by law if necessary—because it changes people’s behavior, or whether it is just a lot of sound and fury that doesn’t change much of anything. Disinformation experts argue that these kinds of campaigns, including what some like to call “automated propaganda,” do have a deleterious effect, but research shows that even the worst disinformation rarely changes people’s minds in any significant way (although in some cases, it can help reinforce things people already believe that are wrong or untrue). And disinformation remains, to some extent, in the eye of the beholder. Not so long ago, users who suggested that COVID-19 came from a lab might have had their Facebook accounts suspended. Now there are plenty of scientists who believe that this is a valid theory about the disease.

The broader question of whether the internet and social media are a negative influence has also been a consistent theme of my time at CJR. Multiple scientific-sounding articles have argued that cellphone and social media use have caused widespread anxiety, depression, and mental health problems among users, particularly teenage girls. This is a plausible-sounding phenomenon, and yet the majority of the research that has been done to date shows no such correlation—and, in some cases, actually shows that smartphone and social media use is a net positive for teens. I think, in general, that we should be wary of theories that tie complex human relationships to a single cause, whether it’s Instagram use or Russian troll farms engaging in what Facebook likes to refer to as “coordinated inauthentic behavior.”

As for whether the internet and social media are good for anyone at all, that question, too, has been an undercurrent of my work for CJR—and even before that. I confess that when I started writing about the social Web at the Globe and Mail, a daily newspaper in Toronto, in 2004 or so, I was convinced that it had the potential to change the world for the better. (I even cofounded a conference called Mesh that tried to explore all the ways it might do so.) I helped the Globe and Mail set up a Twitter feed and a Facebook account and do live-blogging and open itself up to reader comments; I even started a wiki to crowdsource reader insights about politics. At Gigaom, I wrote about how Twitter and Facebook helped enable the Arab Spring in Egypt, among other phenomena. Networked information seemed to have so much potential.

Unfortunately, the next decade or so—including most of my time here—would provide plenty of evidence that social media, like the internet itself, enables all of the good things about people but also all of the bad things. There was Gamergate, which in many ways helped give birth to the alt-right and its obsession with using freedom of speech to harass and abuse people via social media; then there was the rise of QAnon and conspiracy theories about Hillary Clinton and a sex-abuse ring. Facebook inadvertently helped to enable what many international observers have described as a genocide in Myanmar. To some extent, social media gave birth to the human chaos engine known as Donald Trump, a man who embodies Steve Bannon’s motto that the best route to informational success is to “flood the zone with shit.” (Unfortunately, this tactic often works on journalists and media outlets that should know better.)

Was I too naive about the positive impact of social media, and too dismissive or unaware of its negative effects? Absolutely. (In my defense, so were Dorsey and Mark Zuckerberg.) And yet what can counter these kinds of negative effects but people using those platforms and tools and technologies for good instead of evil? Perhaps that’s part of the reason I haven’t vacated Twitter (or X) despite my misgivings about Musk; if we all abandon these platforms to the bad actors and bots, how does that help? (I should note that I am also there because I enjoy the memes.) Maybe flooding the zone with positive content can counteract the effects of those who are flooding the zone with the other stuff. I’ve also been encouraged by the rise of Threads, Meta’s Twitter clone, and its experiments with the networked “fediverse,” including open-source platforms such as Mastodon and BlueSky, although none of them have really replaced Twitter as of yet.

Despite the challenges the media faces—whether it’s social algorithms, declining ad revenue, or AI-driven fakes—I still believe that there has never been a better time to be a journalist. The journalism business may be tanking, but the practice itself has never been more robust. At what other time in history could someone have started writing and within a matter of weeks reached tens or even hundreds of thousands of readers—and be making a living solely from subscriptions? I.F. Stone would have sold his soul for something like that. I am no I.F. Stone by any means, but I would like to thank all of you for reading me over these seven years, and for helping me draw attention to some of the issues that matter. I hope we can stay in touch in other ways. Onward!