What I would say to the Oxford Union about social media

I got an unusual email the other day from someone representing the Oxford Union, a fairly prestigious student-run debating society based (not surprisingly) at the University of Oxford in England. The Union was founded by students in 1823 and, despite the name, is separate and distinct from the actual student union at the university. According to Wikipedia, the Union's first recorded debate was about the topic of Parliamentarianism vs Royalism during the English Civil War. The Union has hosted interviews and addresses by world leaders, celebrities, and others, and its roster of past speakers includes Winston Churchill, Albert Einstein, Mother Teresa, and Barack Obama. The email noted that these past speakers have also included more contemporary celebrities such as Morgan Freeman and Shakira (I wonder what that address was like) as well as famous world leaders like His Highness the Dalai Lama.

Once it had listed all of these previous celebrities, the email asked if I would be willing to take part in a debate sometime during the current term at Oxford (known as the Hilary term, in honour of St. Hilary of Poitiers). The topic? Whether social media ought to be owned not by huge private corporations, but by the public. By way of background, the Union is modeled on the British House of Parliament, with banks of seats on either side, a speaker who introduces the topic — phrased in the form of "This House believes" or "This House argues" — and then a series of speakers for each side of the debate, some from within the Union and some from outside it. Members vote by leaving through one of two doors, one labeled "Ayes" and one labeled "Noes," and the vote is recorded for posterity. You can see photos of it here. The Union also has a series of very cool old buildings, including a library and a private club (naturally).

I'm not telling you all of this just to brag — although I would be lying if I said I wasn't flattered to be invited. Unfortunately, there is virtually no chance I will be in England around the time they would like me to take part in the debate, and there was no mention in the email about absorbing the cost of two flights to London (since my wife would never let me go without her). As a formerly hard-working but not especially talented journalist, I don't have the resources to fly to the UK to present a 15-minute address to the Union, much as I would like to join the exalted pantheon of speakers. So consider this preamble more of a scene-setter, if you will, for this piece, in which I plan to address the topic of the debate that Oxford sent me. Here's how it was described:

This House Would End Private Ownership of Social Media Platforms: What happens when the digital town square is owned by billionaires, driven by opaque algorithms, and governed by no one you ever voted for? In a world where a few private companies shape what you see, what you know and how you think, the question is no longer whether social media directs society but who should direct social media itself. This debate asks whether private ownership should end. Would public or democratic control protect us from disinformation, manipulation and addictive design, or would it crush innovation, free expression and the unruly creativity that defines the internet? Join us for a high-stakes confrontation over power, freedom and the future of our online world. If social media is the new public square, should the public own it?

As it happens, the issue of corporate control of this vast networked communications technology we have become so used to is something I've been thinking about for quite awhile, and have written about in a number of different ways over the past decade or so, which could explain why the Union came up with my name. One of the first pieces I wrote was part of a package I produced at Gigaom, the San Francisco blog network that now exists in name only (which is why I am linking to my personal archive of content at Authory). The package was called Open vs. Closed, and in it I tried to look at the benefits and advantages of open models — open-source software, non-paywalled content, etc. — vs the closed, or walled-garden model that Apple and others have pursued over the years. Is the closed model a better way to make money? Probably. Apple is a great example of that, with a market value of $4 trillion. But is it better for society?

Note: In case you are a first-time reader, or you forgot that you signed up for this newsletter, this is The Torment Nexus. You can find out more about me and this newsletter in this post. This newsletter survives solely on your contributions, so please sign up for a paying subscription or visit my Patreon, which you can find here. I also publish a daily email newsletter of odd or interesting links called When The Going Gets Weird, which is here.

Open vs closed

Here's how I described the open vs. closed dichotomy in 2010 for the package I did for Gigaom, in terms of a technological approach — which is a little like the private vs public debate, I think, but using slightly different terms:

Advocates of open say their approach is best because it maximizes creativity, by allowing the greatest number of people to contribute to a project. Open standards, they say, also allow startups to develop new products and services rapidly and cheaply, because they don’t have to wait for a single controlling entity to give its approval, and they don’t have to pay licensing fees. The closed model, according to critics such as Harvard Law School professor Jonathan Zittrain, leads to situations like the one that Kindle owners found themselves in last year, when Amazon deleted a book they had bought without even asking their permission (ironically, the book was George Orwell’s “1984”).

Although my post was mostly about technology, I think the same general principle applies to media as well, and to social media. In the case of the former, is it better to be the Wall Street Journal or the Financial Times, and have a hard paywall, or would we be better off if more publishers took the approach of The Guardian, which has no paywall per se but focuses on encouraging donations? We've seen this dynamic play out in social media as well: Facebook has been more or less closed from the beginning, and if anything has become even more closed over time, to the point where there is talk that the company might charge users for posting links. Reddit was one of the original social communities, along with Digg, and it was open (to a fault sometimes) but since the main goal is now to make money after its IPO, it is getting more and more closed.

There is no question that being closed can generate a greater short-term payoff in financial terms. But in terms of broader social impact, I would argue that open models can be even better — take Linux, the open-source software project. Microsoft has made more money from Windows, but its reach and influence pales next to Linux, various flavours of which run on nearly every supercomputer and server farm around the world. Android is another good example: although it is controlled by Google, a private corporation, it is an open model, and the number of Android devices far outweighs Apple and every other manufacturer. Or take WordPress: it is open-source software, and it powers almost half of the world's content websites. Wikipedia is another great example of an open model that has succeeded to the point where it is the default information source for millions of people on a number of topics, including breaking news.

There are flaws to open models, of course. Both Linux and WordPress have suffered in the past from having a widely-revered but also arguably too-controlling founder — in Linux's case, creator Linus Torvalds, and in the case of WordPress co-creator Matt Mullenweg. There is no question that WordPress is a great phenomenon, and Matt deserved a lot of the credit for that, but as I've written before for Torment Nexus, I think he suffers from hubris occasionally and decides to wage war on competitors or make unilateral decisions that aren't in the best interests of the broader community. I think Matt believes that only he can really say what those best interests are, but I (and others) disagree. In the same way, of course, the behavior of corporations like Twitter can be distorted by CEOs and founders who lose their minds for a variety of reasons.

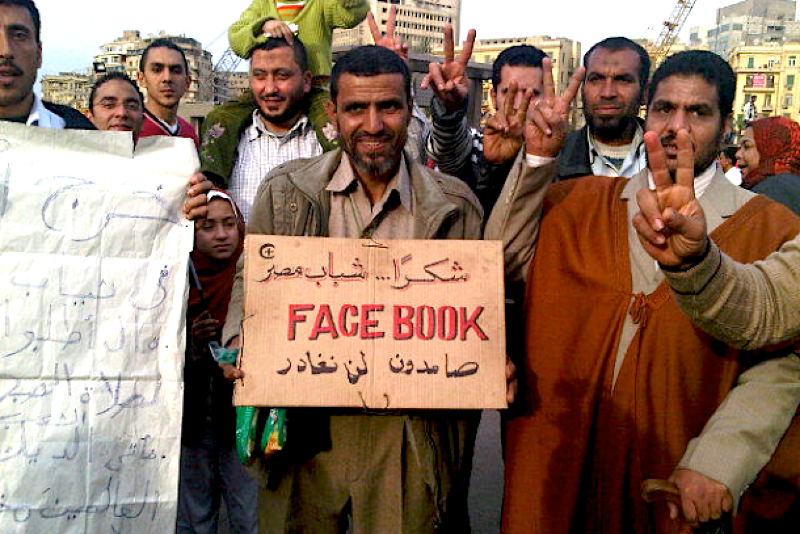

The dangers of closed models for social media — especially those run by global corporations like Facebook and Twitter, which are effectively controlled by a single individual — should be abundantly obvious by now. But just to recap some of the big negatives briefly, these networks decide which information you should see and when, whether by direct control or via their algorithms, so if Facebook doesn't want you to see videos of violence in Syria it can remove them. If it doesn't want to show you news articles in Canada because it is mad about a new law, it can refuse to do so. At the extreme, this kind of control helps fuel the kind of kleptocratic broligarchy that seems to be running the US government right now, not to mention global genocides like the one in Myanmar, which Facebook helped enable by ignoring the obvious signs of rising hate speech.

What kind of internet do we want?

In the realm of traditional media, you could argue that the New York Times and the Journal have similar powers to control what we see and to some extent what we believe to be true, except that they aren't globe-spanning behemoths with trillion-dollar market caps. There is also a very powerful open model for journalism that can counteract much of this, thanks to entities like the BBC, NPR and others (although I should note that the health of public journalism is very much in question, to the point where the Corporation for Public Broadcasting just voted to shut down due to a lack of funding). I argued a number of years ago that there is an alternate universe in which Twitter didn't choose the proprietary model, and became a kind of infrastructure for the social web with an open API, similar to the systems that support email or the web itself.

A useful thought experiment might be to consider what the web might be like if Tim Berners-Lee had decided to commercialize HTML and HTTP instead of giving it to the world for nothing. In the same way that the web browser was commercialized by Marc Andreessen and Jim Clark at Netscape and eventually became a bloated parody of its former self, so the web would likely have been splintered and turned into the same kind of internet that AOL and Compuserve had hoped to make it: an information superhighway controlled by mega-corporations like telecom companies and software makers, where everything costs money and you get a tiny corner to customize as your own.

My friend Ethan Zuckerman has written about public social media in a number of different venues, both while he was with MIT and since he has moved to the University of Massachusetts, where he wrote a paper titled "The Case for Digital Public Infrastructure." In it, Ethan looks at the development of other technologies such as radio and television, and the different models that countries like the US and Britain chose for managing those technologies and the disruption they caused. In the end, Zuckerman argues for a tax on digital advertising giants, revenue that could fund an alternate public model for social media (Emily Bell at the Tow Center at Columbia has argued for a similar type of tax to help fund journalism) . The important question is: would an open model work?

One question that has bothered me for some time — ever since I first started thinking about the open vs closed dichotomy — is why open alternatives, whether in media or social media, aren't more popular. In social media, there are open-source Twitter alternatives like BlueSky (which I've written about before) and Mastodon, which is effectively the Linux of the social web. But neither of them has gained much traction outside of a core group of devoted users. Why is that? In part it's because of network effects, but I also think it's because proprietary models tend to be easier (one of the things that doomed blogging). Walled gardens like Apple's or Facebook's can also be a lot more inviting — there are gates to keep out the rif-raff, and someone to pull the weeds. Here's how I put it in 2012:

The question we are left with, as John Battelle and other open-web supporters such as Dave Winer have argued, is “What kind of internet do we want?” And unfortunately, the answer to this question is far from obvious. Advocates of the free and unfettered internet may not want to admit it, but plenty of users don’t seem to care whether something is a walled garden or not — all they care about is whether they can get what they want when they want it, and as easily as possible. In many cases, users don’t seem to really care about privacy and other considerations either, if the services they get are appealing enough. All of which suggests that fighting for an open web doesn’t just mean beating up on giant entities like Google and Facebook and Amazon — it means figuring out how to convince users that they should care.

Got any thoughts or comments? Feel free to either leave them here, or post them on Substack or on my website, or you can also reach me on Twitter, Threads, BlueSky or Mastodon. And thanks for being a reader.