Why Google deserves to lose its advertising antitrust case

Last month, Google was hit with a significant ruling in an antitrust case involving its dominance in the search business: A federal judge in the District of Columbia ruled that the payments that Google makes to Apple and other companies in return for being the default search engine — payments that totaled more than $20 billion dollars last year — are an unfair restraint on competition. Judge Mehta found that Google controls almost 90 percent of the search market, a figure that rises to nearly 95 percent for mobile devices, and that the company has used its monopoly to charge higher prices. “Google is a monopolist, and it has acted as one to maintain its monopoly,” Mehta wrote.

Less than a month later, Google is in court for a second antitrust trial, this one involving its control over online advertising. The case was launched in January of 2023 by the Department of Justice and eight states, including New York, New Jersey, and California (nine more states joined later). It states that Google "corrupted legitimate competition in the ad tech industry by engaging in a systematic campaign to seize control of the wide swath of high-tech tools used by publishers, advertisers and brokers to facilitate digital advertising." The government concluded its main arguments last week and asked the court to force Google to sell off some of its ad technology.

Google deserves to lose

Predicting the outcome of this kind of trial is difficult at the best of times, but this one is especially difficult for a couple of reasons, including the fact that the way the courts interpret antitrust law is a moving target, combined with the reality that the online ad market is a complex animal — so complex that it makes online search look like a kid's birthday party. That gives Google a lot of wiggle room to argue that it doesn't have a monopoly in the legal sense of the word, and that even if it does, it hasn't done anything anticompetitive to maintain that monopoly (simply having a monopoly is not illegal under US antitrust law — the government has to show that a company obtained the monopoly through illegal means, and/or used illegal methods to maintain it.)

All that said, however, if I were placing bets, I would bet that Google is going to lose this case, just as it lost the search case — or, to hedge my bets a little, I would argue that it deserves to lose this case. The actual remedies the court may hand down are a separate issue (the Department of Justice famously won its case against Microsoft in 1998, but failed to get the court to agree that the company should be broken up; in the end, Microsoft just had to agree to modify some of its behavior.) But there is no question in my mind that the DoJ has shown incontrovertible evidence of anticompetitive behavior by Google.

Note: In case you are a first-time reader, or you forgot that you signed up for this newsletter, this is The Torment Nexus. You can find out more about me and this newsletter in this post. This newsletter survives solely on your contributions, so please sign up for a paying subscription or visit my Patreon, which you can find here. I also publish a daily email newsletter of odd or interesting links called When The Going Gets Weird, which is here.

The complex ad market

This case is more difficult to grasp than the search case because the ad market is a lot more arcane. In a nutshell, publishers use an ad server to manage the space they have available for ads (the DoJ estimates that Google’s ad server controls 87% of the US market for these and 91% of the market globally.) In order to fill ad space, the right to do so is auctioned off through a real-time exchange (the DoJ estimates that Google’s ad exchange controls 47% of this market in the US market and 56% globally.) Large advertisers use a "demand-side platform" or DSP that decides what exchanges to bid on and for how much, and ad networks that automate the buying and placement of those ads (the DoJ alleges that Google's controls 88% of this market in the US and 87% globally.)

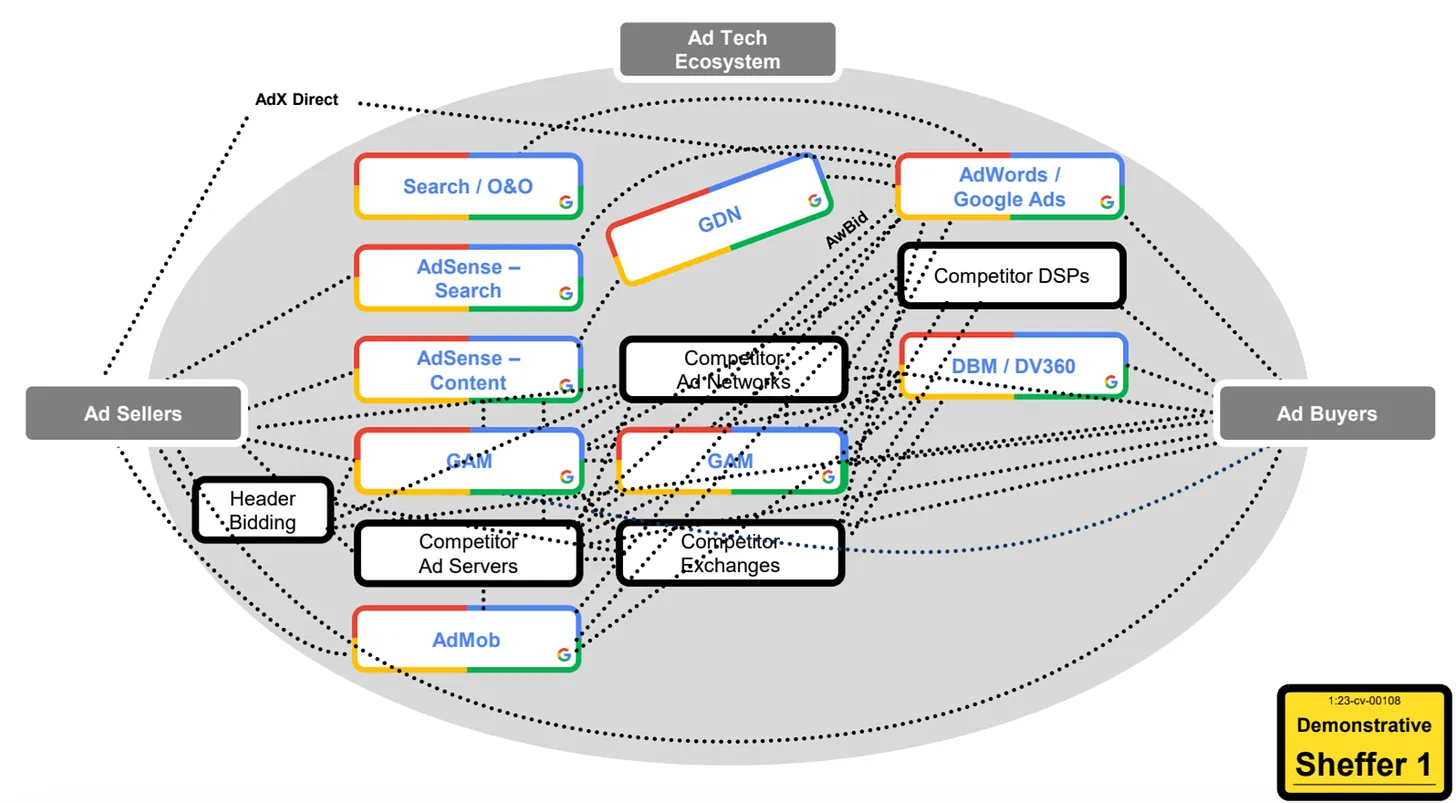

Sound a tad confusing? It is. And it only got more confusing when Google tried to simplify it by constructing a model of the online ad ecosystem in court in real time, joining bits of the market that it controls together with dotted lines. The result was a somewhat hilarious effort the judge reportedly described as a "spaghetti football," according to Marketecture, a site written by a former DoubleClick executive and ad industry expert. Here's what it looked like:

Remember that this is Google's attempt to define the market in its own defense! And yet, in the first segment, the company controls five out of six of the elements, and in the other two segments it controls two out of four elements and two out of three. The spaghetti football actually seems to help the DoJ's argument rather than hurting it. It's important to note that the government is not arguing that Google's monopolies in these markets are de facto illegal, it is arguing that they are tied together in a way that makes it functionally impossible for publishers and advertisers to avoid using them.

According to the DoJ, Google’s ad server automatically calls on Google’s ad exchange to bid first, which allows Google to win more often than not — in part because websites want exclusive access to advertisers who use Google Ads. Brian Boland, who ran Facebook's ad business, compared this to Google getting to "pick the best apples out of a crate" before anyone else can have a look at them. After an auction ends, Google is able to see the result through the information sent to its ad server, allowing it to preempt the winner by offering a lower amount. One DoJ expert said this was like having an auction with sealed bids, but letting Google open the envelope at the end.

Ironically, one of the most compelling descriptions of the DoJ's case came from Jonathan Bellack, a former Google product manager, who asked in a 2016 email: “Is there a deeper issue with us owning the platform, the exchange, and a huge network? The analogy would be if Goldman or Citibank owned the NYSE.” That is exactly what the DoJ and other critics say is wrong with the way that the online ad market is structured — what is supposed to be an open market is effectively rigged in Google's favor, because it is playing both sides (on the stand, Bellack dismissed his email as “late night, jet-lagged ramblings”).

Like owning a browser and an ISP

I don't want to suggest that I am 100 percent buying the DoJ's case, but I think it is strong enough to win, arguably stronger than the search antitrust case that it just won. In that case, Google was found guilty for (among other things) paying Apple and others to make its search engine the default, just as Microsoft was found guilty for (among other things) forcing PC makers to make its web browser the default. According to the DoJ, Google ties the leading ad server and the leading ad exchange and the leading demand-side platform together in a way that forces advertisers and publishers to use them. It's as if Microsoft not only owned the PC market and the web browser market, but also the top website host and the internet infrastructure to connect them.

Google has only started its defense, but we know most of what it is going to argue because it did so in an advertising antitrust case that was launched by the state of Texas and 14 other states in 2020, which is still making its way through the courts. In the past, the company has written that the lawsuit "ignores the enormous competition in the online advertising industry," and accuses the Justice Department of ignoring rivals like Facebook and Amazon to make its case sound more compelling. It calls the case "a flawed argument that would slow innovation, raise advertising fees and make it harder for thousands of small businesses and publishers to grow."

Tom Blakely, a Boston-based lawyer, has been covering the Google trial on a site called Big Tech On Trial, funded by the American Economic Liberties Project, a nonprofit that focuses on antitrust. As he points out, market definition "is going to be the fulcrum" for this case. The government is making the case that there are three distinct markets — ad servers, ad exchanges, and ad networks — and that Google ties them together in an unfair way. Google, however, wants the court see these as three aspects of a single online ad market, one in which everyone from Amazon to TikTok competes.

Google also appears to be trying to redefine the legal grounds of the case by arguing that it doesn't have any duty to allow competitors to use its ad server, ad exchange, or ad platform. As Blakeley notes, the government is alleging illegal tying, but Google "wants to make this a 'refusal to deal' case." In the end, Google seems to be saying: "We have an ad server and an ad exchange and an ad platform, and we make them work together because it helps our customers get lower prices, so it isn't illegal" (I'm paraphrasing, obviously.) This is similar to Google's argument in search, which was "we have the best search engine, and that benefits consumers, so the ends justifies the means."

Not many average web users care a whole lot about the ad tech case, I would be willing to bet, because they don't use ad servers and real-time "header bidding" for ads, nor do they know (or care) what a demand-side platform is. Many may assume that the online ad market is a giant scam — which in many ways it is — and the ones playing in it are mostly a pack of animals motivated largely by greed (again, hard to disagree). But that doesn't mean there aren't consequences to Google's dominance of the market, including the impact of ad costs on small publishers and websites. If the market were more competitive, then the things that rely on it might also be more competitive.

Got any thoughts or comments? Feel free to either leave them here, or post them on Substack or on my website, or you can also reach me on Twitter, Threads, BlueSky or Mastodon. And thanks for being a reader.