Google's control of the web could be coming to an end

It's been hard to avoid the US government's antitrust case against Meta lately, since CEO Mark Zuckerberg spent three days in front of the cameras in Congress, testifying about his company's alleged anti-competitive tactics. But another equally large Silicon Valley behemoth is arguably in an even worse position, having lost not one but two landmark antitrust decisions, about two different aspects of its business. That giant is Google, which the courts say has engaged in illegally anti-competitive conduct in both its search and its online advertising operations. The government is expected to argue that Google should be forced to sell off significant chunks of its business, including its market-leading Chrome browser, and those sales — if and when they actually come to pass — could change the way that online publishing works in some fundamental ways.

The latest ruling against Google came last week, when Judge Leonie Brinkema of the US District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia said in a 115-page ruling that Google had acted illegally to maintain a monopoly in online ad technology. The Justice Department and a group of states sued the company in 2023, arguing that its monopoly over various parts of the online ad industry allowed the company to charge higher prices and squeeze out potential competitors. Judge Brinkema said the government proved that Google "willfully engaged in a series of anticompetitive acts to acquire and maintain monopoly power in the publisher ad server and ad exchange markets for open-web display advertising." She added that Google "tied its publisher ad server and ad exchange together through contractual policies and technological integration, which enabled the company to establish and protect its monopoly power.”

Brinkema said that Google's exclusionary conduct "substantially harmed [its] publisher customers, the competitive process, and, ultimately, consumers of information on the open web." According to Danielle Coffey, president and CEO of the News/Media Alliance, the decision marks “a big day for the news media industry after enduring so many years of extortionist fees and diminishing ad revenue from Google’s abuse of its market power." Google, not surprisingly, begged to differ: Lee-Anne Mulholland, vice president of regulatory affairs, said in a statement that publishers "have many options and they choose Google because our ad tech tools are simple, affordable and effective,” and that the company "won half of this case and we will appeal the other half."

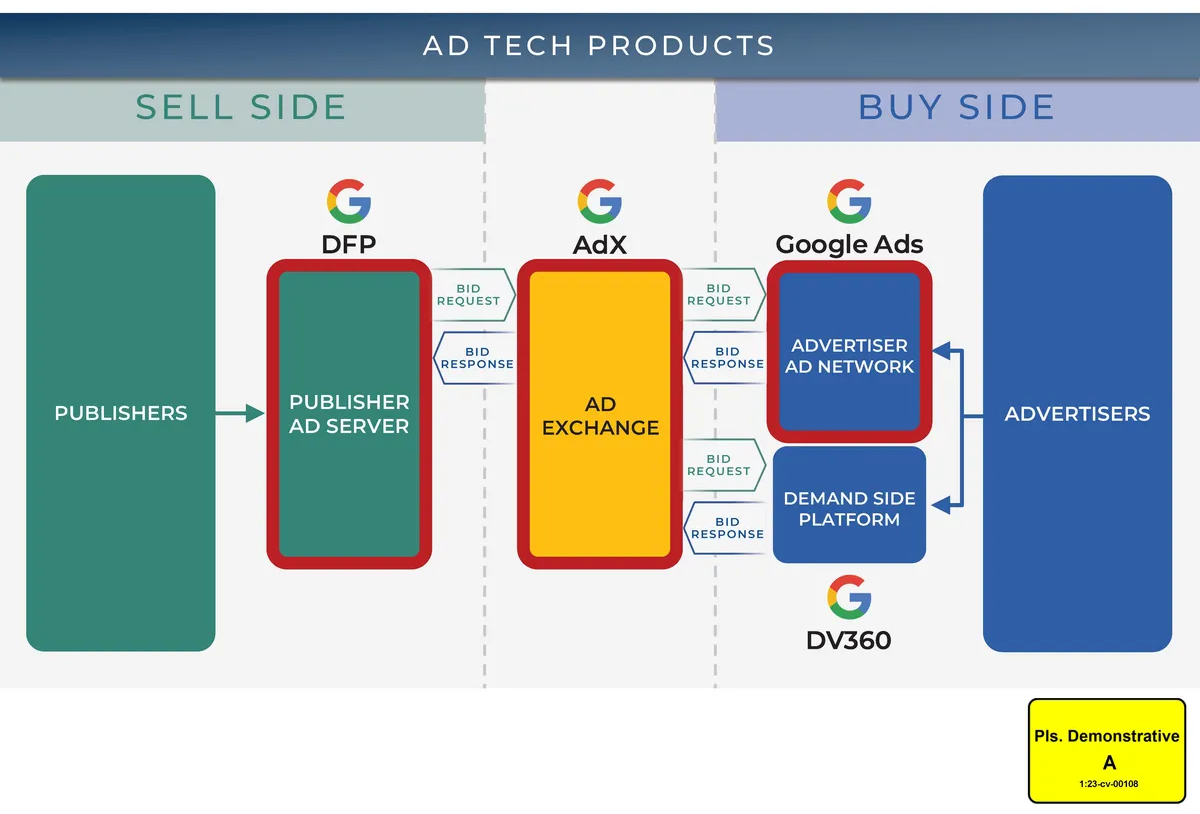

As most people probably know, online publishers carry digital ads to help finance their operations. Those ads appear as a result of an auction process that in some cases is carried out in the milliseconds between when a user clicks on a link and when the site loads. Publishers use a tool called an ad server to manage their ad space, and it interfaces with online ad exchanges, which manage the flow of ads; advertisers in turn use tools on the other side of the transaction, including ad networks, to provide the ads. It's multibillion-dollar industry, one that is crucial to the lifeblood of many publishers, and Judge Brinkema ruled that Google has an illegal monopoly on two pieces of that triangle: the ad servers that publishers use, and the ad exchanges where they find and bargain for access to digital advertising.

Note: In case you are a first-time reader, or you forgot that you signed up for this newsletter, this is The Torment Nexus. You can find out more about me and this newsletter in this post. This newsletter survives solely on your contributions, so please sign up for a paying subscription or visit my Patreon, which you can find here. I also publish a daily email newsletter of odd or interesting links called When The Going Gets Weird, which is here.

Tied together

The government argued that one of the things that made Google's behavior anti-competitive is the way that it tied its various services together, forcing publishers to only use its products, something the courts have ruled is a hallmark of anti-competitive activity. In one of the Justice Department's submissions, an advertising executive wrote in a 2017 email to her boss that "the value in Google’s ad tech stack is less in each individual product but in the connections across all of them." As Bloomberg explained, advertisers using the Google Ads network are only permitted to place bids through Google’s own exchange, AdX (with limited exceptions). In 2020, Google Ads sent bids for 18 million ads to AdX, but only about 3 or 4 million to non-Google exchanges. Certain functions of Google’s ad exchange, including what is called "real-time bidding," are also only available to publishers that use its ad server.

The Justice Department said in its submissions to the court that Google controls about eighty-seven percent of the US market for ad servers — the software that is used by publishers and websites — and about ninety-one percent of the market for that kind of software globally. Google's ad exchange has about forty-seven percent of the US market and fifty-six percent globally, the Justice Department told the court. The government also said that Google's ad network, which many advertisers use to manage the supply of ads, controls about eighty-eight percent of the US market and about the same amount of the global market, but Judge Brinkema ruled that this was not proven to be a separate and distinct market, and therefore Google's share was not relevant to the government’s antitrust case.

The question of market definition is also critical to the Meta case. The Federal Trade Commission argued in filing its lawsuit that Meta controls a significant share of something called the "personal social networking" market, and therefore its acquisition of Instagram in 2012 for $1 billion and its purchase of WhatsApp in 2014 for $19 billion should both be unwound as anti-competitive. However, the company and some of its defenders — including Ben Thompson, who writes a newsletter of technology analysis called Stratechery — argue that "personal social networking" is not a distinct and identifiable market at all, and therefore the government's case should fail because it excludes obvious competitors such as TikTok. I wrote about this for The Torment Nexus recently, and agreed with Ben and others that the government's case is weak.

Judge Brinkema gave both sides in the Google advertising case a week to propose a schedule for the next phase of the case, known as the remedy phase, where the government argues for changes to Google's business in order to correct the illegal conduct. In its statement of claim, the Justice Department asked the court to force Google to sell several pieces of its ad technology business, and the judge could pursue that remedy or could decide that additional remedies are required. Either way, Google is likely to appeal, which means the case will drag on, possibly for years, before it reaches a conclusion.

A feedback loop

Meanwhile, another antitrust case against Google has just entered the remedy phase. The Justice Department argued this week in Washington that Google should be forced to sell its Chrome web browser and make other changes after a court last year found Google had gained an illegal monopoly over internet search by using what the government called a “feedback loop” of anti-competitive practices. The search case was originally filed in 2020 and went to court before Judge Amit Mehta of the US District Court for the District of Columbia in 2023 for an eight-week trial. The government argued that Google's deals with companies like Apple and Samsung to make its search engine the default on most smartphones — deals that cost Google more than $26 billion a year — were designed to rig the market in favor of Google.

In addition to selling Chrome, the government late last year asked Mehta to force Google to stop the company from paying Apple and Samsung to make Google search the default on smartphones, and has suggested that if this doesn't make the search market more competitive within five years, Google should be forced to sell off Android, its mobile operating system, which powers a majority of the world’s smartphones. The Justice Department also raised the possibility that Google's dominance in search could help it dominate the emerging market for artificial intelligence, and that this would be bad for consumers.

Google's lawyers called the government’s proposed remedies “extreme” and “fundamentally flawed,” and argued in court that the company "won its place in the market fair and square.” Google said the changes the Justice Department is recommending would allow competitors to capitalize on Google's hard work and ultimately harm competition in the search market rather than promoting it. But one publishing industry executive said that the more than $20 billion that Google was found to have paid Apple in 2022 to be the default search service on its smartphones “came from the pocketbooks of marketers and from publishers who suffered by not getting the revenue that they should have gotten.”

The cases against Google and Meta are part of a larger movement by government regulators to curb what they argue are the excessive power of major tech companies. The Justice Department has also sued Apple, arguing that the way the company ties its smartphones and other devices together with its online app store have locked in consumers and harmed competition and choice in the smartphone market. And the Federal Trade Commission has sued Amazon, accusing it of using its dominance in online retailing to harm small businesses and online competitors. Observers say President Trump's choices for the head of the FTC and the top antitrust role in the Justice Department indicate that the administration wants to continue to crack down on the market power that large tech companies have. If both Google and Meta are ultimately forced to reshape their businesses, Evelyn Mitchell-Wolff of Emarketer told Reuters, “the digital advertising landscape could be unrecognizable in five years.”

Got any thoughts or comments? Feel free to either leave them here, or post them on Substack or on my website, or you can also reach me on Twitter, Threads, BlueSky or Mastodon. And thanks for being a reader.