If AI helps to kill the open web what will replace it?

If you've been following the news about Google's I/O conference at all, you probably know that it was all about artificial intelligence — and that isn't an exaggeration. Literally every announcement, every feature, and every app demonstration involved AI in some form or another. An autonomous AI agent called Project Astra; an AI-powered agent for writing computer code known as Jules; AI-authored "smart replies" in Gmail; an AI-powered web browsing service called Project Mariner; an AI shopping service that lets you try on clothes virtually; real-time AI-powered translation in Google Meet; an AI-powered image generator called Imagen; an AI-driven video generator called Veo; a service that blends all of these to make movies, called Flow; and of course AI in search, whether through the AI Overview at the top of a regular search, through a separate "AI Mode" search tab, or through the standalone Gemini AI app.

As Casey Newton wrote in his Platformer newsletter, Google didn't explicitly talk about the implications of all of this AI machinery, either for its business model or for the future of the open web, but the conclusions are fairly obvious:

Snap out of this fever dream long enough and you can spot hints of the world that is coming into existence. Gmail is learning how to write in your voice, and will begin to do so later this year. The camera screen will chat with you while you are fixing your bike, telling you what to do every step of the way. NotebookLM will start generating TED talk-like videos of your PDFs for you to watch. An executive on stage says that before too long you will be able to generate a how-to video for almost any subject you like. And while the company continues to protest, it seems obvious that this new world will give you many fewer reasons to visit the open web. Google will generate the things you once searched for, and all the businesses that once relied on those searches will need a Plan B.

Some of you young whippersnappers in the audience may not remember, but way back in the mists of time, when the internet was brand new, Google search came along and at first it seemed like just a great new tool — one that was faster and better than Yahoo and Infoseek and Altavista and Ask Jeeves and all the other early search engines. But what wasn't immediately apparent at the time was how Google would become the cornerstone of a vast, globe-spanning internet-based ecosystem and economy. Websites — whether they were large and institutional, set up by companies, or small and personal, powered by blog software like Blogger or Typepad or WordPress — could publish for next to nothing, and their words and thoughts could reach across the globe, thanks to Google search. This is what we now think of (or used to think of) as the open web.

The open web had more to it than that, of course, since it was built on top of the open internet: the machinery underneath the hood was all open as well, and in most cases it was also free, or close to it — TCP/IP allowed every machine to connect to every other, and HTML allowed browsers to read any site, and RSS allowed website authors to distribute their thoughts to people without browsers. And if you gained enough of an audience, that pool of attention could be monetized, either by Google ads or by other ad networks.

Note: In case you are a first-time reader, or you forgot that you signed up for this newsletter, this is The Torment Nexus. You can find out more about me and this newsletter in this post. This newsletter survives solely on your contributions, so please sign up for a paying subscription or visit my Patreon, which you can find here. I also publish a daily email newsletter of odd or interesting links called When The Going Gets Weird, which is here.

What have we lost?

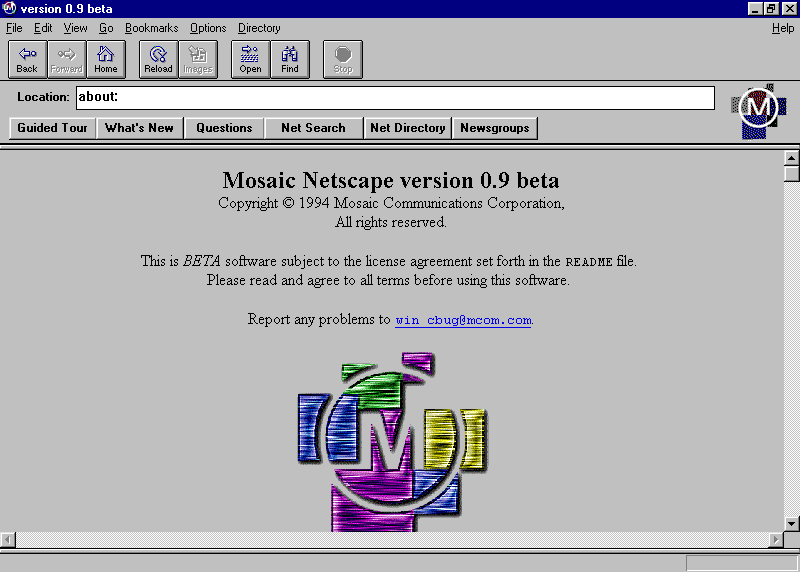

What I've described lasted for a little while, not all that long in the grand scheme of things — maybe 10 years at the most (I wrote more about these early years of the web in a previous edition of The Torment Nexus, on the anniversary of the launch of the first Netscape browser). After that, things started to get big, and to morph into different shapes. Social media apps like Twitter and Facebook and Snapchat and Instagram came along, and they created networks that had little or nothing to do with the web — in fact in some cases, as with Facebook, their owners were åctively hostile to the open web. My friend Anil Dash, who used to work at Typepad and now runs the open-source platform Glitch, wrote eloquently in 2012 about what he called "The Web We Lost," including open standards and an ecosystem of free websites and tools that anyone could use.

Anil made the case that Google advertising was the beginning of the death knell for the open web, writing that in the early 2000s, "because Google hadn’t yet broadly introduced AdWords and AdSense, links weren’t about generating revenue, they were just a tool for expression or editorializing. The web was an interesting and different place before links got monetized, but by 2007 it was clear that Google had changed the web forever, and for the worse, by corrupting links." That may be true, but the ecosystem that Google created also allowed new sites to flourish, and in particular a new wave of digital publishers — sites like AllThingsD, started by Kara Swisher and Walt Mossberg, or Gigaom (where I used to work), started by Forbes writer Om Malik, or Gawker and Mashable and many others.

There were flaws to this model, obviously. One was that digital advertising more or less forced every publisher to think about clicks and pageviews and daily unique visitors, and that in some cases turned business models into a focus on "clickbait" (this was a problem with the old-fashioned publishing business as well, which just wanted to sell newspapers, but the web accelerated it). And as Google came to dominate online advertising, it was able to control the volume and price point of ads to a large extent — one of the reasons why the government argues that Google should be forced to sell some of its ad business, as I wrote in a recent edition of The Torment Nexus — and that left many publishers running what I call the Red Queen's race, in reference to Alice in Wonderland, where Alice says the players have to run twice as fast just to stay in the same place.

But whatever its flaws, that ecosystem generated a fair amount of what I would argue was real value — an environment for news and commentary that was much broader and more diverse than the printed ecosystem. That diversity would soon come to include an increasing number of disturbing and arguably dangerous viewpoints, such as Breitbart or The Daily Stormer, but that's to some extent a separate issue. That's a problem inherent in human nature, not something that was created by the open web or even by Google.

An artefact from an earlier time

In an interview with The Verge, Google's head of search says that the company's search result page — the one we have all grown up with over the past two decades, the one that powered so much of the web I've described — was an artefact of a different time. In other words, something that is coming to an end:

“I think the search results page was a construct,” she says. The way we’ve all Googled for two decades was largely a response to the structure of the web itself: web pages in, web pages out. Good AI models are now able to get around that structure, and find and synthesize information from lots of sources. When I ask Fox and Reid what this might mean for the web, and for the millions of website owners and publishers that have long depended on Google to send them traffic, Fox says he’s convinced the rise of AI is not the end of the open web. “I deeply believe this is an expansionary moment,” he says. “The death of the web has been 25 years coming, and it’s not happening. The web is growing.”

Is the web growing? Perhaps. But while it may be the case that some people are clicking on the links in a Google AI search, a number of recent examples have shown that lots of businesses are using AI tools themselves to create content, and that trend is likely to continue. The prospect that creates is a kind of content ourobouros, where the snake of AI search is eating its own AI-created tail. How much of the growth that Google is seeing is from automated websites or services to other automated websites and services? Not only that, but while web traffic might be growing, it seems difficult to believe that the number of small, independent, sel-published or small-group websites are growing. Everyone spends their time on TikTok or Facebook or Reddit or Discord. Anyone who wants to publish seems to have moved to Substack, a proprietary platform.

There's no question that services like Substack and Ghost — the open-source service I use to publish this newsletter — and Patreon and others have helped create an ecosystem of individual writers and publishers who in many cases can support themselves through their work (I am not yet one of those people, so please upgrade your subscription or contribute through my Patreon!), but that is a small slice of what the open web used to be. What replaces the rest of it? Facebook isn't doing it and clearly doesn't want to — it wants to be TikTok, and so do Instagram and YouTube. So is the future just made up of fashion influencers and AI avatars and dance competitions and video clips? Perhaps. At one time we were worried about television taking over and shortening people's attention spans, but TikTok makes TV look like the collected works of Shakespeare.

In a recent edition of his Stratechery newsletter, Ben Thompson wrote about the rise of what he called the "agentic web" — a web where autonomous or semi-autonomous AI agents create content and/or crawl and index it for their own purposes — and the death of the ad-supported web. Thompson argued that:

With AI intruded or being included in every aspect of search, "every leg of the stool that supported the open web is at best wobbly: users are less likely to go to ad-supported content-based websites, even as the long tail of advertisers might soon lose their conduit to place ads on those websites, leaving said websites even less viable than they are today — and they’re barely hanging on as it is!"

What comes next?

Thompson also quotes Eric Seufert from MobileDevMemo on what the changing nature of the online content ecosystem means:

I’ve heard arguments that, because Google suppressed competition in open web advertising markets, those markets should flourish when Google’s monopoly is broken. But my sense is that this ignores two realities. First, that consumer engagement has shifted into apps and walled gardens irreversibly. And second, that Google was keeping the open web on life support, and the open web’s demise will be hastened when Google no longer has an incentive to support it. What happens to the open web when its biggest, albeit imperfect, benefactor loses the motivation to sustain it?

This is the fly in the ointment of an AI web. Microsoft and others are trying to create open standards in the spirit of TCP/IP and HTML and RSS — things like MCP (model content protocol) and NLWeb (a markup layer), which make it easier for AI agents to find content, answer questions, perform actions on a user's behalf, etc. But this could just make the web over into a place that is useful only for agents, who are acting on behalf of other agents, who are theoretically acting on behalf of a user somewhere. As Nilay Patel of the Verge pointed out in his interview with Microsoft's chief technology officer, Kevin Scott:

That is the piece that on the web right now seems most under threat, the underlying business dynamics of I start a website, I put in a bunch of schema that allows search engines to read my website and surface my content across different distributions. What I will get in return for that is not necessarily money — what I’ll get is visitors to my website, and then I’ll monetize them however I choose to: selling a subscription, display ads, whatever it is. That’s broken, right? What’s going to replace that in the agentic era? What’s going to make that worth it?

Thompson thinks this is the perfect opportunity for micro-transactions, enabled by cryptocurrency such as "stable" coins (assets backed by real-world currencies such as the US dollar). Perhaps Ben is right and this is the future; but what if there is nothing left for them to enable but transactions between AI agents over content created by other agents? As he puts it, the ecosystem "depends on humans seeing those webpages, not impersonal agents impervious to advertising, which destroys the economics of ad-supported content sites, which, in the long run, dries up the supply of new content for AI. OpenAI and Google are clumsily addressing the supply issue by cutting deals with news providers and user-generated content sites like Reddit [but] this ultimately won’t scale."

I should note that I am encouraged by the development of open-source and open-platform services like Ghost and Bluesky and Mastodon and other elements of the "fediverse" (and by odd experiments like this one). I am a big believer in what my friend Mike Masnick calls "protocols not platforms," and of user control over algorithms and other elements of social media. But that is just part of a truly open web of content, and I feel as though large parts of it are either dying or in decline. What should we do about it, if anything? Great question!

Got any thoughts or comments? Feel free to either leave them here, or post them on Substack or on my website, or you can also reach me on Twitter, Threads, BlueSky or Mastodon. And thanks for being a reader.